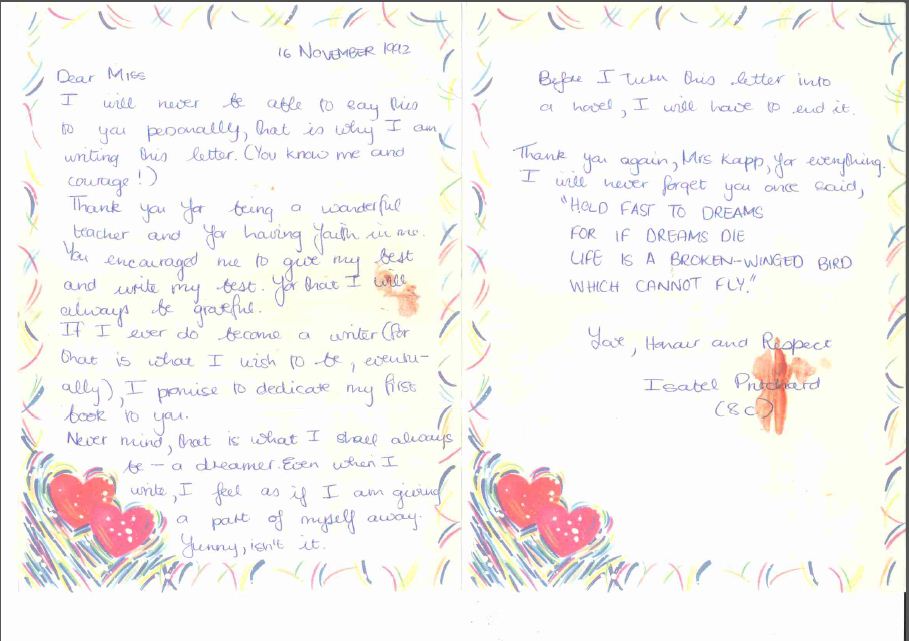

A “Dear Miss” letter surfaces in the Kapp household, circa end-May into June 2015.

women in and beyond the global

analyzing and changing the status of women in households, prisons and cities

A “Dear Miss” letter surfaces in the Kapp household, circa end-May into June 2015.

The dishonesty of the liberalism of Gareth van Onselen must be exposed. He writes that ‘the ANC is sick’, but he is unwilling and unable to see the role his beloved liberal ideology played in the ANC’s increasing dissoluteness, conservatism and authoritarianism.

For Van Onselen the ANC’s ‘sickness’ can be seen in it ‘losing support, wracked by infighting, held hostage by division, a slave to an economically regressive mind-set, unable to organise internal conferences and denuded of talent as thinkers and an older generation desert it in the face of contemporary demagoguery.’ He also mocks Jacob Zuma’s turn towards traditionalism and religion. He does not ask why this is happening to the ANC right now.

Why, at this particular point, is the ANC – divided along unprincipled, tenderpreneurial lines – turning back to its Stalinist authoritarianism of the 1960s to the 1980s and its traditionalism of the 1910s to the 1950s? This is the question the Van Onselens cannot confront.

The rise of tenderpreneurialism, traditionalism and authoritarianism are good reasons to be worried, but we do not live under a traditionalist or Stalinist authoritarian political system. We are living under a liberal, constitutional political system. It is the effects of South Africa’s liberal, constitutional framework that is directly responsible for what is happening to the ANC.

In the 1990s the ANC adopted liberal constitutionalism and specifically South Africa’s constitution. It did not completely abandon its previous ideological postures but blended it with liberal constitutionalism in ways that often lacked consistency. However, its commitment to writing, promoting and implementing the constitution during this period cannot be doubted. What was the effect of this?

South Africa’s constitution was carefully designed to protect the basic structures of capital. By doing that, by protecting wealth, it inevitably protected the main means through which it is generated – cheap and unpaid black labour. By acceding to capital’s demands for liberalising the economy, the ANC oversaw the intensification of South Africa’s structural racism. White wealth and its opposite pole, black poverty, grew to make South Africa the most unequal society in the world.

South Africa’s constitution was never designed to cure the main sickness of Apartheid and actually made it worse. The ANC was now confronted with rampant inequality and explosive growth in the tensions and resistance this engendered. At the same time, the neo-liberalisation of the state-business nexus had completely embroiled it in corruption, tenderpreneurialism and factional conflicts based on it. It is under these pressures, that are a direct result of the liberal constitutional regime, that the ANC started looking back to its past for possible solutions to the multiple crises it was confronted with.

It is not possible to understand the ANC’s return to Stalinist authoritarianism and traditionalist conservatism without understanding it as the outcome of its turn to a liberal constitutionalism that prioritised the interests of white wealth. For people like Van Onselen the ANC’s sickness appear out of nowhere, because he needs to deny the oppressive nature of our liberal constitution. The constitution contained its own demise. It ostensibly sets out to protect the wealth of the rich and the rights of the poor. This cannot be done. The ANC is realising that. It is therefore, to some degree, abandoning the pretence of protecting the rights of the poor.

Yes, the ANC is morally sick. But so is South Africa’s liberal constitutionalism and so are its promoters such as Van Onselen.

(Photo Credit: The Guardian / Rex Features) (Image Credit: Roar Magazine)

Nonhle Mbuthuma

There’s an uprising, once again, in Pondoland, on the eastern coast of South Africa, and, as before, it concerns the violence brought on local populations by the State and its international partners, all in the name of `development’ and national improvement. This time the “resistance is distinguished by the prominence of women.”

Nonhle Mbuthuma has grown up in the struggle for a decent and better life, and for a State where one can’t say, “There’s too much `democracy’ in this democracy.” Her story goes back a ways.

From 1960 to 1962, the `peasants’ of Pondoland waged a mighty revolt against the Bantu Authorities Act and, more generally, against the ravages of apartheid on rural populations. Almost immediately after the Mpondo Revolt, Govan Mbeki researched, wrote and published South Africa: The Peasants’ Revolt, which showed the centrality of peasant and rural struggles to the national aspirations for emancipation and justice. Mbeki ended the chapter “Resistance and Rebellion” prophetically: “The Pondos paid dearly for their failure to ensure the safety and security of their forces at the height of the struggle. And in this they were not alone. Zululand and Zeerust suffered similarly, although on a smaller scale. But the people do not bear sufferings, such as they bore when the army occupied the Transkei, without becoming steeled in their determination to regroup, re-examine their methods of struggle, develop new ones, and retain the spirit that seeks forever for freedom.”

That was 1964. Forty years later, in 2004, mining companies began applying for permission to mine in the Mgungundlovu area of Amadiba Tribal Adminstrative Area in Pondoland. The area, also known as Xolobeni, boasts the second highest diversity of flora in South Africa, one of 26 places on earth with such a rich concentration of species. It’s commonly described as gorgeous, pristine and heavenly.

Local residents have been involved in developing eco-tourist sites, but the prospect of mining threatens everything. At first, people thought the mines could bring jobs and services, but discussions with other communities and the behavior of mining corporations soon disabused many of that notion. And so, in 2007, residents formed the Amadiba Crisis Committee.

The State claims the mines are good for business, even though this particular mine will only be open for 25 years, and then the agricultural and environmental economies will just have to work it out … again. Good for whose business?

The Committee argues for the environment, due process, Constitutional rights, respect for the graves of the elders, sustainable economic development. From the Committee’s inception to today, Nonhle Mbuthuma has been a leader. Throughout, Mbuthuma has taught that the Constitution protects everyone, and especially rural people because of their histories of struggle.

In 2009, Nonhle Mbuthuma made clear that an assault on the land is an assault on the people’s history: “Asilufuni Uphuhliso lwenu! [We don’t want your development!] […] If this mining takes place and the government issues a licence in this area, there will be war. There will be an uprising as it was in the [last] Mpondo Revolt.”

And this is today: “My forefathers died for this land. If I’m going to die, I’ll not be the first one.”

The Pondo Uprising continues to cast more than a long shadow across South Africa and beyond. It lives, inspired and informed by young women, like Nonhle Mbuthuma, who carry it forward and retain the spirit that seeks forever freedom.

(Photo Credit: Daily Maverick / Lucas Ledwaba / Mukurukuru Media) (Video Credit: Ryley Grunenwald / Vimeo)

In November last year, Loveness Mudzuru and Ruvimbo Tsopodzi filed a suit in Zimbabwe in which they charged that the situation of “child brides” violated girls’ constitutional rights. They named Justice Minister Emmerson Mnangagwa, Ministry of Women’s Affairs, Gender and Community and the Attorney General’s Office as respondents responsible for implementation of the Customary Marriages Act, which allows for girls to be married at 16.

Age prohibitions are like speed limits. There’s the letter of the law and then there’s the car on the road. Ruvimbo Tsopodzi, now 18, was married off at 15: “I’ve faced so many challenges. My husband beat me. I wanted to stay in school but he refused. It was very, very terrible. I want to take this action to make a difference. There are a lot of children getting married.” Tsopodzi is the mother of one child.

Loveness Mudzuru, now 19, was married off at 16. By the time she was 18, she had given birth to two children: “Young girls who marry early and often in poor families are then forced to produce young children in a sea of poverty and the cycle begins again. My life is really tough. Raising a child when you are a child yourself is hard. I should be going to school.”

Across the border, in South Africa, the Western Cape High Court this week upheld the conviction of a 32-year-old man on various charges related to the trafficking and rape of a 14-year-old Eastern Cape girl. He tried to argue that the girl was not kidnapped and that there was no rape, but rather they were husband and wife, by a customary practice known as ukuthwala.

The Court rejected the man’s appeal and, more broadly, the argument that customary or traditional law allows for violence against girls and women: “The practice of ukuthwala has in recent years received considerable public attention… inasmuch as its current practice is regarded as an abuse of traditional custom and a cloak for the commission of violent acts of assault, abduction and rape of not only women but children as young as eleven years old by older men.”

Speaking of so-called child marriages, African Union Chairperson Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, commented: “We cannot downplay or neglect the harmful practice of child marriage, as it has long-term and devastating effects on these girls whose health is at risk.”

While these stories describe girls living in poverty and struggling against physical and structural violence, they also speak of the courage and determination of precisely those girls, who speak for themselves. They say they deserve education, health, well being, safety, and peace. They say as well that individual and collective dignity and justice begin and end with informed consent. They say NO! to all forms of coercion and exploitation of girls, and boys, and they mean it.

(Photo Credit: Girls Not Brides)

In South Africa this week, 48 women living with HIV and AIDS responded to the indignity and abuse of forced sterilization. Represented by Her Rights Initiative, Oxfam, and the Women’s Legal Centre, 48 women who had suffered forced sterilization in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal came forward and lodged a formal complaint. These 48 `cases’ were from 1986 to 2014. These 48 women are the tip of a rumbling volcano. They are the faces and bodies of gendered inequality in South Africa and beyond. They represent the untold numbers of women living with HIV and AIDS who have been forced to suffer one indignity after another. They represent all women in national and regional economies where women’s bodies are viewed as consumables with ever declining values.

The women tell their own stories, for example, Zanele, who was 19 years old and 38 weeks pregnant: “As I was thinking about it, [the doctor] turned to this lady who was with her, I think she was an intern, and said we [referring to HIV-positive women] were a problem to the hospitals, we give birth all the time … at that time I felt guilty as a patient. Then [the doctor] came back and asked me if I wanted to be sterilised and I said yes.”

There is another, connected story, as told by Dr Ann Strode from the University of KwaZulu-Natal. In 2012, Dr. Strode published a study published that examined the situation of forced sterilization of women living with HIV and AIDS. At the time, the research team believed that the practice had more or less ended by 2006, with the national rollout of antiretroviral drugs, or ARVs. In the present group of 48, more than half of the violations took place after 2006. Dr. Strode and her colleagues were surprised by the findings.

Consider the story of surprise. When those who are the most informed and the most engaged, when the advocates and the organizers, think the story is over, it takes the subjects, the women themselves, to step forward and `surprise’ the public consciousness out of its slumber. Two of the cases were from last year, and one has already resulted in a civil suit in Gauteng.

Some talk about the double stigma women living with HIV and AIDS suffer: being HIV positive, being unable to have children. But there’s a third stigma: having failed the nation-State. Women who are HIV positive are viewed as failed citizens. That’s why they can be treated this way, despite Constitutional and legal protections to the contrary. The Department of Health says forced sterilization is not department policy, but it is practiced, in the open, regularly.

Each of those 48 women represents tens and hundreds of other women living with AIDS, and each of those 48 women represents thousands and tens of thousands of women who struggle and organize in the unequal and violent spaces between policy and practice.

“End this violation on women’s bodies! My body, my rights, my womb, my choices.”

(Photo Credit: The Star / Chris Collingridge)

Gloria Kente is a live-in domestic worker in Cape Town. In 2013, her employer’s then-boyfriend got angry with her, allegedly grabbed her, spat in her face, and screamed a racist epithet at her. Kente called the police and had him charged with assault and a violation of her human and civil rights. She called him out for hate speech and harassment. When the man tried to extend `an apology’, Kente said, “NO!” If an apology meant not going to court, not having the State fully involved, then Gloria Kente wanted no part of it. Last November, the man was found guilty, and on Friday he heard his sentence.

The man was sentenced to two years house arrest, 70 hours of community service “in the service of Black women”, successful completion of various programs addressing substance abuse, prohibition from owning any firearms and from using any substances.

Gloria Kente was not in court on Friday, but her attorney said she was happy with the sentence.

As so often happens, the news coverage of this case focuses largely on the man. Employers disrespecting and abusing domestic workers is not news. Employers disrespecting and abusing domestic workers’ rights under the law is also not news. The news is that around the world, domestic workers are saying “NO!” to abuse. Around the world domestic workers are on the move, organizing, advocating, going to court and winning civil and criminal cases, organizing unions, consolidating power for domestic workers and for women workers generally. That’s the story.

In Hong Kong today, a court found that Erwiana Sulistyaningsih’s employer had indeed abused her. Her employer was found guilty of criminal intimidation, grievous bodily harm and wage theft. Again, the story is not the employer, but rather Erwiana Sulistyaningsih’s refusal to accept the veil of secrecy that enshrouds household labor. Erwiana Sulistyaningsih said “NO!” to the violence of like-one-of-the-family, and, instead, said “YES!” to workers’ right, women’s rights, migrants’ rights, humans’ rights, and every configuration thereof. As Erwiana Sulistyaningsih explained, after hearing the verdict: “To employers in Hong Kong, I hope they will start treating migrant workers as workers and human beings and stop treating us like slaves, because as human beings, we all have equal rights.”

In Lebanon, immigrant and migrant women domestic workers are organizing a union. In Pakistan domestic workers have formed their first trade union, partly as a response to increasing violence against domestic workers and partly as a response to the affirmative recognition of their combined rights and power. Last December, the Pakistan Workers Federation formed the Domestic Workers Trade Union. Of 235 members, 225 are women domestic workers. Sumaira Salamat, in Lahore, is a member: “It’s only in the last year-and-a-half that these women have finally realised the importance of what it means to become a united force. We want to be recognised as workers, just like our counterparts working in factories and hospitals are. We would also like to get old age benefits like pensions when we retire; but most of all we want better wages and proper terms of work.”

Everywhere, women domestic workers are on the move.

Remember that when you read about this court case or that decision and the abusive employer receives all or most of the attention. The days of employers owning history are over. Gloria Kente, Erwiana Sulistyaningsih, Sumaira Salamat are shaking the world up. Remember their names.

(Photo Credit: IOL / Jeffrey Abrahams) (Photo Credit: Philippe Lopez / Agence France – Press / Getty Images)

For the past week, women from mining communities in South Africa, Mozambique, Botswana, Zambia and Zimbabwe have been meeting in Johannesburg to share their experiences, strengthen their networks, map and take the way forward. They have been brought together by WoMin, African Women Unite Against Destructive Resource Extraction. They have had enough of environmental devastation, corporate predation, and State violence. They are sick and tired of living and dying in communities and households where everyone is tired, sick, and dying. And they have had enough of being ignored or silenced. They come together to say, Now is the time! They come together to make NOW the time.

In an hour long interview this week, Samantha Hargreaves, Regional Coordinator of WoMin; Nhlanhla Mgomezulu, Coordinator of the Highveld Environment Justice Network; and Susan Chilala, Secretary of the Rural Women’s Assembly, in Zambia, laid out the program. Generally, the women are calling on the State to divert its massive investments in the infrastructure of fossil fuel extraction into alternatives, particularly solar, wind, tidal, and thermal, all plentiful in the Southern African Development Community, SADC, region. All of the countries are already investing great sums of money to make mines happen. The women say: Make something else happen; something sustainable and renewable that will meet the challenge of growing consumption in growing economies.

This diversion would mean that the State would have to reconsider its comfortable relationship with those few who make huge profits at the expense of the many. This would also mean, the women said pointedly, that politicians, such as Cyril Ramaphosa in South Africa, would have to address their complicity as shareholders and leaders in the mineral extractives sector.

The majority of the interview describes the impact of coal mining on local communities. Susan Chilala explained that coal mining attacks women small scale farmers most viciously. She described the impact of coal mining on farming and food security. She talked about the impact on women when their space is taken over by an industry that is so deeply male dominated, from top to bottom.

Nhlanhla Mgomezulu described the impact on women in the South African Highveld: “We women are the ones who suffer most.” Women suffer as individuals, in that their own health is endangered by poisoned water, air, and land, but they suffer even more as principal caregivers of the community. When the children are sick, women work more intensively. When the men return from the mines with asthma, kidney failure, tuberculosis, injuries and more, women are work more intensively. And this labor is `free’ and it’s 30 hours a day, 8 days a week, for life. If that’s not slavery … what is?

Last year, Greeenpeace published a report, which looked at Witbank, in Mpumulanga, in which they found that Witbank has the dirtiest air in the world. This is the gift of coal as a mainstay of `development’: “Sonto Mabina … works at a small tuck shop that’s just a short walk from her home in an informal settlement over the train tracks outside Witbank, in Mpumalanga. She’s lived here for 25 years, arriving well before the three coal washeries that now surround her house … Sonto Mabina, or Katerina as she likes to be called, lives with her husband, Andries. Their house has no electricity or water and Katerina uses a coal stove to cook their suppers, the black plumes of smoke clouding their home. A municipal truck brings water once a week, but most say it’s too polluted to drink. If you can afford to, you buy bottled water in this area of the country; if not, you boil it like Sonto does and you hope for the best. `Dust is my main problem,’ she says. `Every time my child goes to the hospital it’s because of the dust. The doctors say his chest is full of it. The doctors asked me where I lived and I told them. My other child also has problems with his nose because it is always running – the dust affects him too.’ It’s an everyday problem here.”

The women who have gathered in Johannesburg are saying NO to that everyday. They are engaging in a public dialogue, breaking down barriers, transforming isolation into community, teaching as they learn, and they are demanding a better present. Not a better future, a better present. They have lived too long with politicians and others ignoring them. They are demanding that the State take climate change, the environment, community health and wellbeing, and women seriously. African women are standing their ground and more. They are organizing and on the move. The time is now!

(Photo Credit: Mujahid Safodien / Greenpeace)

Gloria Kente

From Hong Kong to Qatar to Greece to the United States, domestic workers and women cleaners are under attack. They are under attack because they are women. In South Africa this year, domestic workers and women cleaners have confronted the attack head on.

Delia Adonis works as a cleaner in a mall in Cape Town. Last month, Adonis saw five men attack a sixth. She called the police, who intervened. She then went to the parking lot, where the five men encircled her, knocked her to the ground, and beat her. Throughout the assault, the men used racist and sexist epithets.

Adonis called the police and laid charges on the five men. It turns out they’re UCT students. Adonis claims that the police came to her and offered her money to drop the case. The officer allegedly said that the men were afraid of being kicked out of school. Adonis rejected the offer, and all it represented: “I’m really angry about this. I’m traumatised and still in pain. These youngsters verbally abuse us every weekend, and now this? I’m a mother of six – how would they feel if someone beat up their mothers like that? There was so much blood pouring from my face I couldn’t see. When I washed my face. I just thought to myself: ‘Boys, you can run but I leave you in the hands of the Lord’.”

Cynthia Joni works as a domestic worker in Cape Town. One morning, Joni was walking to work, when a white man leapt out of his car, slapped and threw her to the ground. She screamed, and he drove away. He was later identified and charged. His `explanation’ was that he mistook Cynthia Joni for a sex worker and `snapped.’ To no one’s surprise, it turns out that Cynthia Joni is not the first woman he’s assaulted. Now others are coming forth.

While the toxic mix in both the physical violence and then the subsequent violence that passes for explanation are important, the women’s response is more important. Domestic workers, sex workers, women workers reject the violence and call on the State to address it … forcefully and immediately.

Gloria Kente is a live-in domestic worker in Cape Town. Last year, her employer’s then-boyfriend got angry with her, allegedly grabbed her, spat in her face, and screamed a racist epithet at her. Kente called the police and had him charged with both assault and a violation of her human and civil rights. She called him out for hate speech and harassment. When the man tried to extend `an apology’, Kente said, “NO!” If an apology meant not going to court, not having the State fully involved, then Gloria Kente wanted no part of it.

Today’s stories echo the past. Over six years ago, four white students at the University of the Free State videotaped their assault on five cleaners, Mothibedi Molete, Mankoe Phororo, Emmah Koko, Nkgapeng Adams and Sebuasengwe Ntlatseng. The video went viral, as did disgust, and the cleaners, four women and one man, fought back. This June, the five cleaners launched their own company.

Today, however, domestic workers and women cleaners are making demands on the State. Domestic workers and women cleaners reject the protectionism that would see them as a separate class in need of help. They are workers with rights, women with rights, and humans with rights. As women workers increasingly demand their civil, labor, and human rights be respected, they consolidate power. The struggle continues.

(Photo Credit: IOL)

Love is all around

Love is all around

is my lyrical response

to a Vukani letter-writer

from out yonder KTC

Where is love

in the townships

is the question asked

(amidst partying and drinking

round our social grant days)

Love is all around

I declare as I ramble

in and about Site C Khayelitsha

A bustling Saturday morning

down Govan Mbeki Road

to the Whizz ICT Centre

for their Youth Centre Launch

and an end-user computer Graduation

(them a small light of hope

all about community sustainability

in a place overshadowed)

Love is all around (too)

at the Moses Mabhida Library

where I’ve been before

for a Reading Competition

(fall in love with learning

says a mural on their wall)

Love is all around

5 happy earthly hours I spend

(language notwithstanding)

as the Youth Centre is launched

and students joyously graduate

Love is all around

What stops you

from making it so too

“Where is love in the townships?” (Letters, Vukani community paper, October 30 2014)

(Photo Credit: Whizz ICT Centre)

Copyright © 2026 · Magazine Child Theme on Genesis Framework · WordPress · Log in