HOTELS SHOULDN’T HURT! is the new battle cry for Workers’ Dignity’s newest campaign against wage theft and working conditions in Nashville’s booming hospitality industry. The member-led workers’ center for Nashville’s low-wage workers, with support from researchers at Vanderbilt University, released a report last week detailing the harsh conditions of labor for the city’s hospitality workers. The Music City has experienced a huge boost to its hospitality industry in the recent years thanks to Nashville’s rise to prominence as an “it” city. However economic benefits have not reached the lowest paid workers in the industry – housekeepers, custodians, and laundry employees.

The findings of the report are saddening, though not shocking. The hospitality industry has a long history of wage theft and abuse among its lowest paid workers. Nashville is no exception. The report finds that nearly 10% of all hospitality workers in Nashville make less than the federal minimum wage of $7.25. 89% of workers worked more than 40 hours a week without receiving fair overtime compensation. As housing and living costs sky-rocket in Nashville, the average wage of a hotel housekeeper, $8.36 an hour, falls far below the national median income. Who are the housekeepers? Overwhelmingly women of color.

In addition to criminally low and stolen wages, the industry is providing little in way of quality safety standards to the lowest paid workers. 39% of employees received no on the job training in handling toxic chemicals. 21% of workers reported that their employees did not provide protective materials such as masks or gloves. 27% of employees reported being injured on the job and 51% of employees are not provided sick days (paid or unpaid). Workers report constantly becoming ill due to long exposure to toxic cleaning chemicals, malfunctioning elevators that lead them to run flights of stairs as they are not permitted in the elevators with hotel patrons, and severe burns that received no attention from hotel management.

Wage theft anywhere cannot be tolerated, but in a city where prices, and buildings, continue to go up, it is crucial that every worker has access to a fair wage and safe working environments. As Workers’ Dignity claims, Nashville is in the midst of a crisis. You may donate to Workers’ Dignity here and remind the Music City that HOTELS SHOULDN’T HURT!

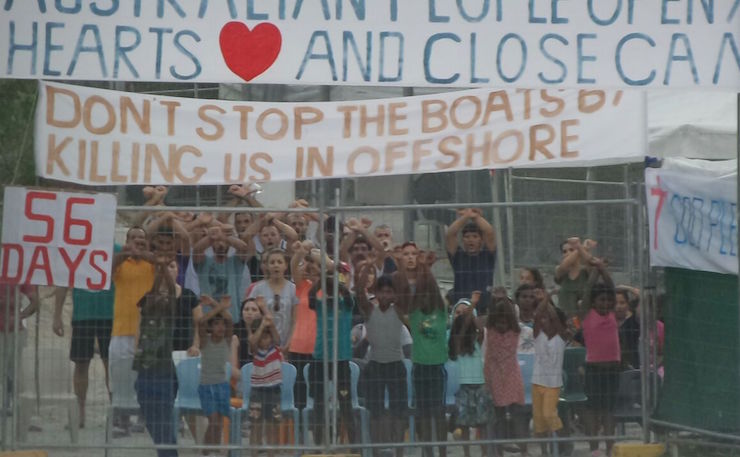

(Photo Credit: Workers’ Dignity)