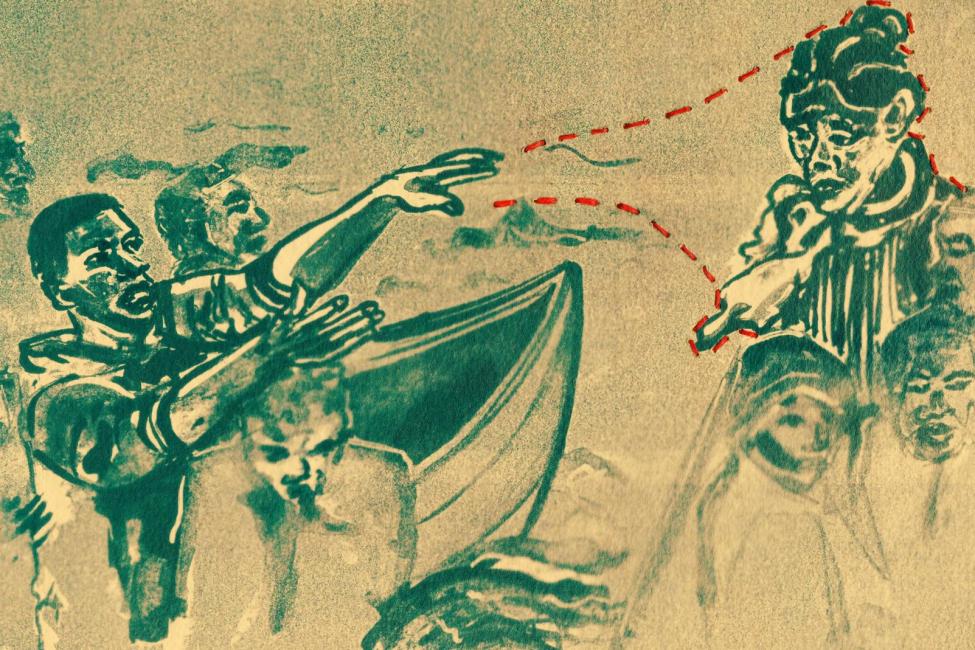

Thousands of family members continue to search for a missing migrant.

This is how 2021 ends. A boat filled with 120 Rohingya Muslim women, children, men – 60 women, 51 children – was on its way from Myanmar to Malaysia. Those in the boat hoped that when they reached Malaysia, they would be given sanctuary. On Sunday, the boat engine failed and the boat started to leak, off the coast of Indonesia. At first, the Indonesian government wouldn’t let the refugees in. Finally, after days of international and local pressure, on Wednesday, the government relented and gave permission, but, they explained, only because the situation on the sinking, overcrowded boat was “severe”. Today, Friday, the boat was towed into harbor, and people began to disembark. The rescue, in heavy rain and high seas, took a grueling 18 hours. Why does a government have to explain rescuing people from a sinking boat? Because they are refugees, women, Muslim, Rohingya, and the list goes on. This is how 2021 ends, much as the previous ten and more years.

On December 25, in three separate incidents, three boats filled with refugees capsized. At least 31 people died, and, as of now, scores of people on those boats are still missing. It is the worst Aegean death toll since October 2015.

The next day, December 26, close to 30 people washed ashore in Libya, refugees who had tried to cross the Mediterranean, just so much flotsam from another shipwreck. These corpses capped a week in which at least 160 people, migrants, drowned in shipwrecks off the coast of Libya.

A month earlier, a boat filled with migrants sank somewhere in the English Channel. At least 27 people died. That is the single biggest recorded loss of life in the English Channel. One witness, a refugee who was in another boat that happened into the same waters soon after the first boat sank, recalled, “Our boat was surrounded by dead bodies. At that moment my entire body was shaking.”

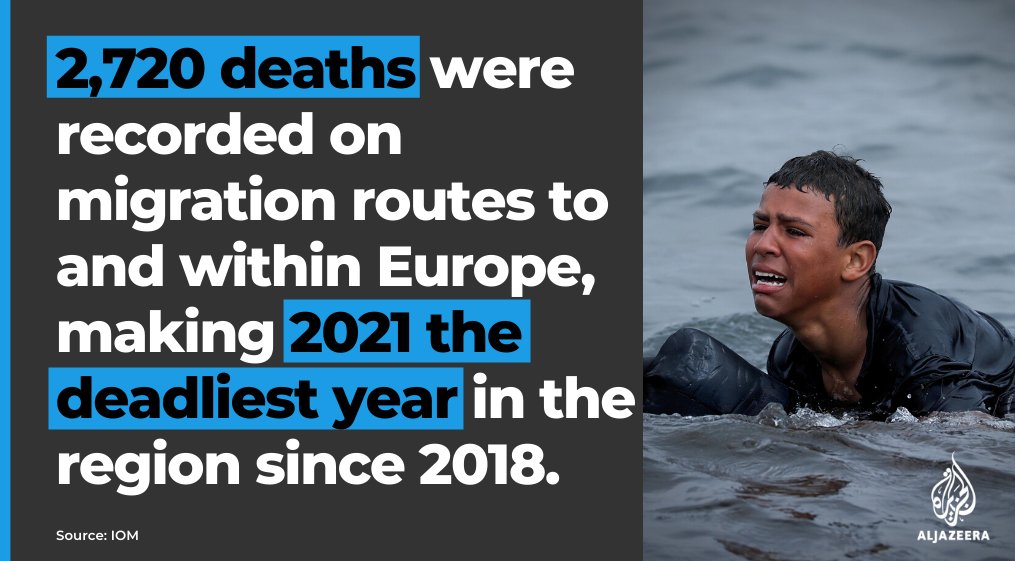

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees that from January to November more than 2,500 people have died in the Mediterranean or in the Atlantic, on their way to the Canary Islands. The International Organization for Migration reports that, as of early December, the 2021 death toll for migrants during migration journeys had surpassed 4,470. They assumed the final tally would be considerably higher, given the lag in time between deaths and the reports thereof. The death toll last year was 4,236. The death toll at the Mexico – U.S. border was already 651, higher than in any year since they started recording, 2014. More migrant deaths were recorded in South America than in any previous year. Europe saw historical highs in migrant deaths. The Atlantic route to the Canary Islands saw the highest death toll in over a decade. According to the IOM, “Mass tragedies involving migration have increasingly become normalized.”

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Image Credit: IOM / Salam Shokor) (Photo Credit: Al Jazeera / Twitter)