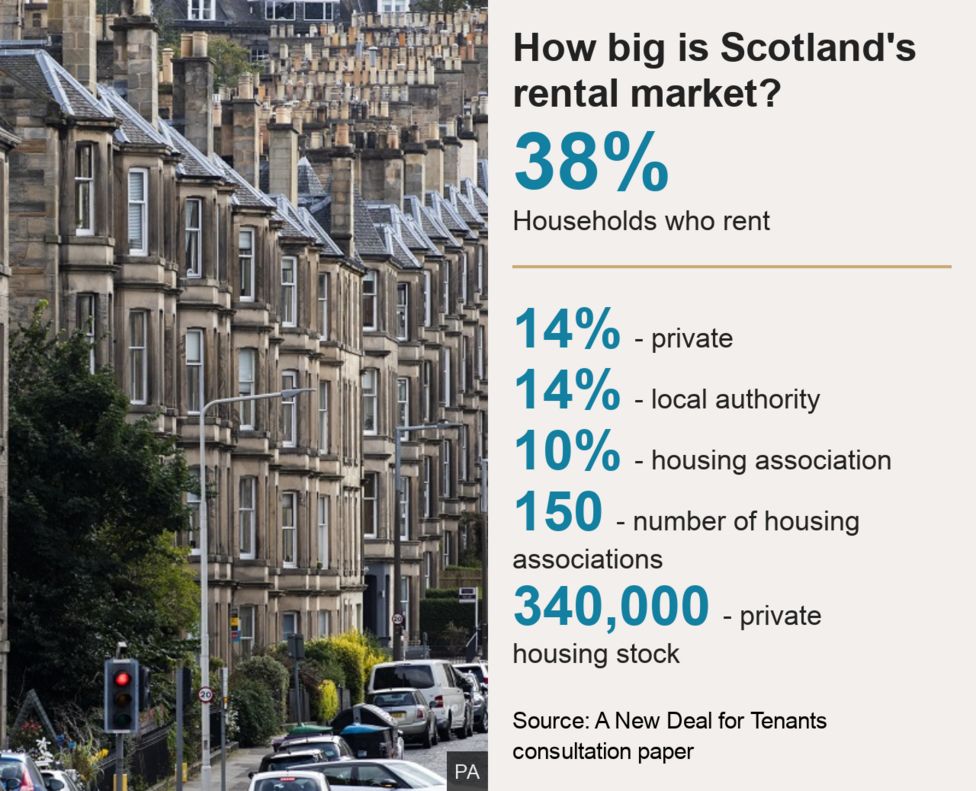

When it comes to evictions and the lack of affordable housing, the Washington, DC, metropolitan area, the DC – Maryland – Virginia DMV, offers a somewhat mixed picture. Overall, affordable housing is critically unavailable. As to evictions, while numbers in all three areas are rising, in DC they’re rising slowly, largely thanks to governmental protections and organizing efforts. In Maryland, though eviction numbers are the highest they’ve been since the COVID pandemic began, they’re not yet approaching pre-pandemic levels. Yet. In northern Virginia, however, eviction “filings appear to be catching up … Statewide, monthly eviction filings as of September are at 87.5 percent of the `historical average.’ Monthly eviction filings have also tripled since January.” In August, Fairfax County blew past the so-called historical average by a full 20%, while Arlington County was 14% below and Alexandria was just 4% below their respective historic averages. Last week, the Virginia Poverty Law Center reported a recent 500% increase in calls, so many calls in fact they had to close the hotline temporarily. That’s the normal, once again, and it’s coming to your town soon. So, what’s going on? The common answer is “the end of protections”, which, as far as it goes, is accurate. But that “end”, that “failure”, is public policy, and It’s succeeding, brilliantly, for a few, if catastrophically, for many.

While much of the attention will focus on northern Virginia, the `return to normal’ is statewide. Between January and June, eviction filings across Virginia rose by 88%: “What tenant advocates see as a budding crisis, landlords view as a return to normal.” Here’s normal: five-day eviction notices. Here’s normal: an eviction filing attached to one’s name, much less an actual eviction, means most landlords won’t even consider the application. Here’s normal: rents in Norfolk, Virginia Beach, Richmond have risen 43%, 37% and 15%, respectively; and Hampton Roads is one of the 20 most competitive rental markets in the United States this year. In Richmond, filings in September were 82% above Richmond’s historic average.

According to the most recent U.S. Census survey, 34.3% of the United States believes they face likely eviction within the next two months. That’s a bit more than one of every three households. In the Washington – Arlington – Alexandria metro area, 43.6% of households surveyed believe they face likely eviction within the next two months. Since that likely distributed, it’s reasonable to think that the numbers in Arlington and Alexandria are higher. You know what it’s called when 44% of a population is displaced? Mass eviction. And what it’s called when whole communities are wiped out?

A recent article on the current chaotic rental market in England offers four reasons for the mess in England, reasons which might afford some insight into the situation in Virginia and the country. First, a shortage of housing, partly market driven largely policy driven, “enables” landlords to ask for skyhigh rents. Second, “greedy landlords”. In the United States, rental markets have been overtaken by corporate landlords who charge much higher rents and, significantly, file for eviction more quickly, more routinely, more often. Third, lack of protection for renters. Here is where the State comes in … or better, has opted to leave the stage. For a period during the pandemic, the United States had tenant protections, and, just like child tax credits and other pandemic relief programs, those protections worked. Thanks to no fault eviction protections, mandatory eviction diversion programs, right to counsel in eviction cases, evictions dropped. State protections helped turn an existential community wide crisis, in which tenants never had a chance, into a reasonable, regulated negotiation, which, in more cases than not, never had to go to court or involve any sort of threat of permanent loss of home for oneself, one’s loved ones, one’s neighbors. In Oregon this week, people facing 50% rent increases are asking their landlords to reconsider. It’s the only thing they can do, throw themselves on the mercy of the landlord. This is the old new normal for what is called affordable housing. From Virginia to Oregon and beyond, we cannot return to normal.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo Credit: Tyrone Turner / DCist / WAMU)