2024 begins as so many previous years have, with reports of and reflections concerning femicides. Here are just a few headlines from the past few days, each followed by the country or countries involved: “Femicides up in Argentina as Milei seeks to weaken protections” (Argentina); “The femicide of Julieta Hernández, a Venezuelan migrant in Brazil, sparks outrage across South America” (Brazil); “SJC Urges Government to Strengthen Preventive Measures Against Femicide” (Georgia); “Pregnant Woman’s Brutal Killing Fuels Femicide Debate in Greece” (Greece); “Kenya femicide: A woman’s murder exposes the country’s toxic online misogyny” (Kenya); “Femicide in Kenya a national crisis, say rights groups” (Kenya); “Exigen justicia para Mafer, víctima de feminicidio en Morelos” (Mexico). In France, early this month, the Minister of Justice announced that, with “only” 94 femicides in 2023, the French government had achieved success. Feminist and women’s organization, using a different method, a method previously used by the French government, found the number to be higher. Even if the number was 94, what kind of “success” is that? Yet again, we are facing a “global femicide epidemic”.

Near the end of last year, the United Nations released its second Femicide Report, Gender-Related Killings of Women and Girls (Femicide/Feminicide): Global estimates of female intimate partner/family related homicides in 2022. The study found that while homicide numbers had fallen, femicide numbers remained the same or rose. Most of the killings were gender-related and committed by intimate partners or other family relations. “The risks of gender-based violence and femicide are only rising as our world is engulfed in conflict, humanitarian emergencies, environmental and economic crises and displacement.” That was in 2022. What does one imagine 2023 and 2024 will look like? Finally, “women and girls in all regions across the world are affected by this type of gender-based violence.” What else is there to say?

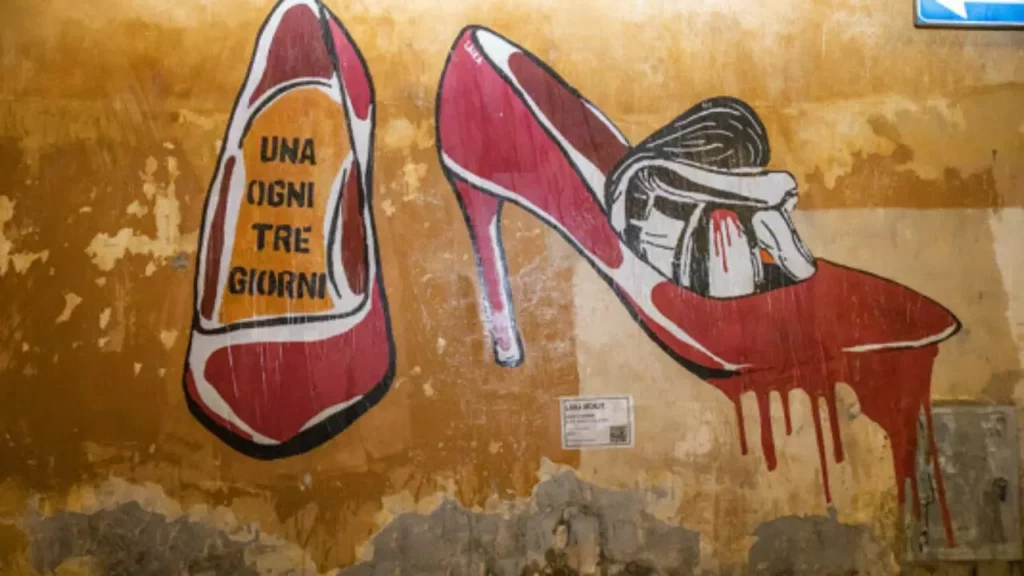

Quite a bit, actually. “While the overwhelming majority of male homicides occur outside the home, for women and girls the most dangerous place is the home.” For women and girls, the most dangerous place is the home. During the pandemic, in every part of the world without any exceptions, the number and rate of femicides increased. Well, the pandemic is over, but the number and rate of femicides continue to increase, or, at the very least, remain at the elevated levels. Why? The causes are many, but one overarching reason, along with patriarchy, is government indifference. For example. Italy passed laws ten years ago and invested considerably large amounts of money, and yet the number and rate of femicides remained relatively stable. Why? According to a recent report, the Italian government put all of its money in attending to victims and survivors of femicide, and little on prevention. The title of that report is “PREVENZIONE SOTTOCOSTO: La miopia della politica italiana nella lotta alla violenza maschile contro le donne”. Low-cost prevention: The myopia of Italian politics in the struggle against male violence against women.” Myopia is a form of blindness, but this `short-sightedness’ is willful.

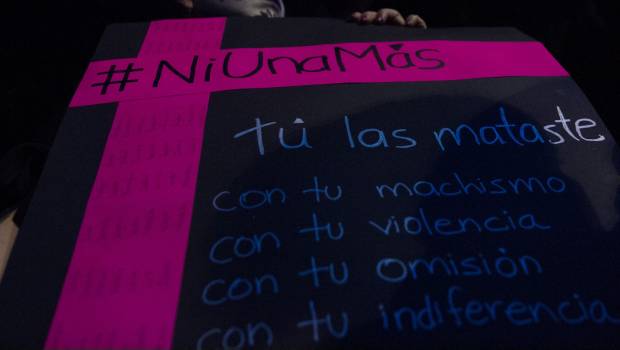

Until domestic violence is seen as a priority, femicides, in raw numbers and rates of commission, will continue to rise, while governments will find new methods of counting and declare success, if not victory. Around the world, this year will see a storm of national elections. Watch to see where domestic violence, violence against women and girls, and femicide figure in the various campaigns. Remember, ten or one hundred or one thousand fewer is not good enough. #NotOneMore #NiUnaMas #NiUnaMenos

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Image Credit: “Una Ogni Tre Giorni” by Laila / Wanted in Rome)