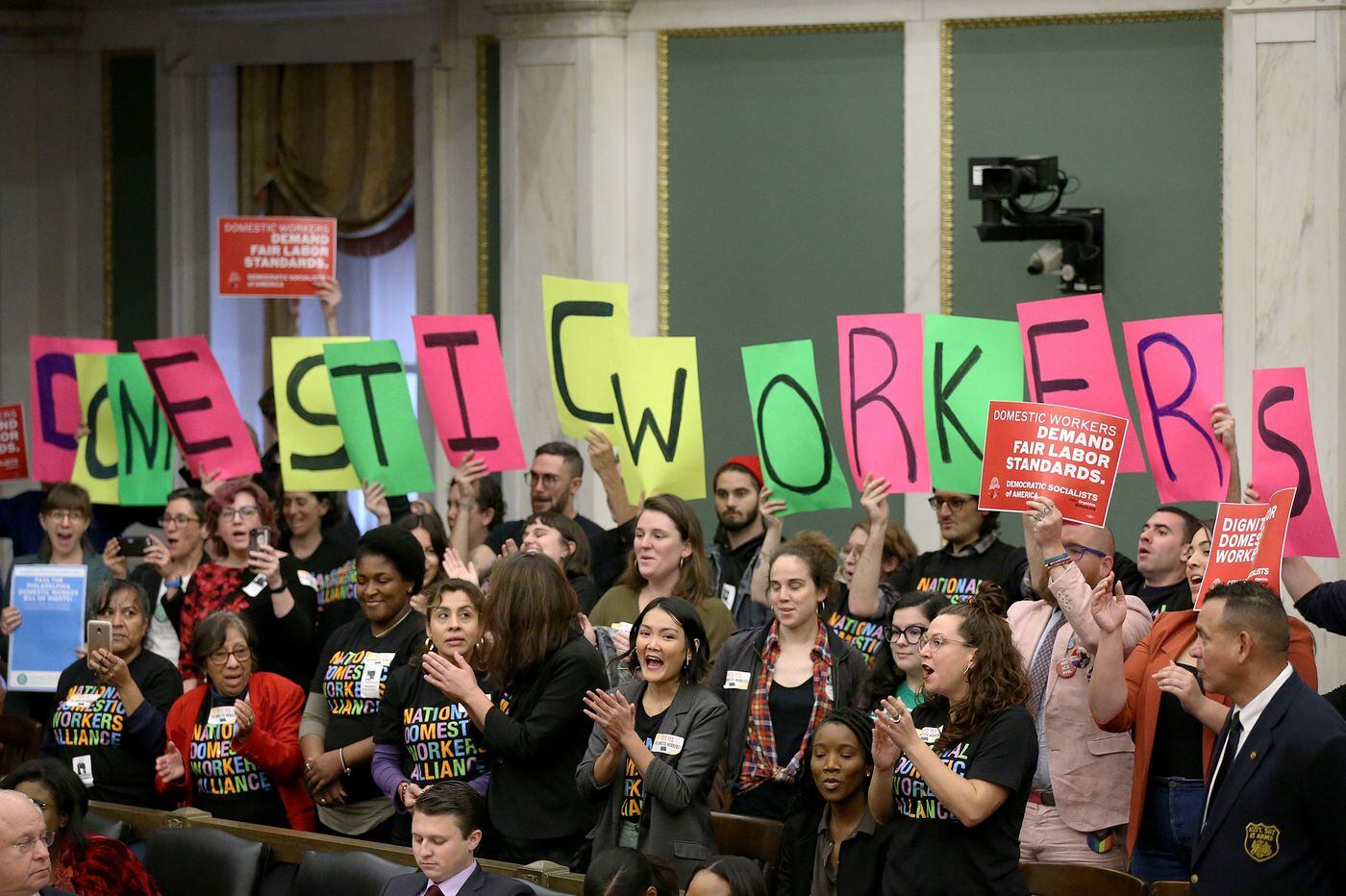

Domestic workers and supporters demands respect and justice.

As of November 7, 2019, 900 female domestic workers have returned from Saudi Arabia to their home country of Bangladesh. They returned before the end of their contracts, many of them citing physical, mental, and sexual abuse as their reason for fleeing. Interviews with 110 returnees revealed that “86 percent did not receive their full salaries, 61 percent were physically abused, 24 percent were deprived of food and 14 percent were sexually abused.” Many blame the prevalence of abuse on Saudi Arabia’s Kafala, or sponsorship, system, which is present in many west Asian countries and binds a domestic worker’s status to an individual employer or sponsor for the duration of their contract. In effect, the worker’s ability to live and work in the country is completely dependent on their sponsor, creating a dynamic ripe for exploitation. Many workers don’t have the resources to seek help, and face retaliation and deportation if they do.

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) continues to blame these domestic workers for their own abuse. According to the Kingdom, the stories told by domestic workers returning to Bangladesh are “nothing but hoaxes and are being spread to give a bad name to the country,” and, again according to the KSA, Bangladeshi workers leave Saudi Arabia due to their inability to adapt to the fast-paced Saudi economy. In response, Bangladesh’s government plans to “better train” the workers it sends abroad, in an attempt to prevent further incidents.

This is a truly insidious form of victim blaming, implying that these workers, most of them women, would not have been abused if only they “knew better.” Beyond the KSA’s refusal to acknowledge the suffering of these workers, Bangladesh’s implicit agreement that the workers are at fault makes them complicit in the abuse. Rather than protect these women, Bangladesh would rather continue to grow their labor exportation economy. On November 14th, Dr AK Abdul Momen, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, defended his Ministry’s lack of action, saying that “only 53 female workers died out of 220,000 female workers currently working in the KSA.” Apparently, the government feels that a few deaths are worth the economic growth their labor provides the country.

A coalition of Bangladeshi Progressive Women’s Organizations has demanded the government free women from repressive situations abroad and stop sending female workers to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia altogether. The movement has gained momentum since Sumi Akter, a Bangladeshi maid, returned home. While still in Saudi Arabia, Sumi Akter made a video pleading for help, describing the extreme abuse she suffered; the video went viral. Many of the organizations have spoken out condemning the minister’s speech, emphasizing how every death is significant and another call for action. No worker’s death, they say, is insignificant.

This coalition shows no signs of backing down, with more women returning and new stories of abuse being shared daily. One can only hope that with continued pressure placed on the government, Bangladesh will eventually act to ensure these domestic workers gain safety and justice.

(Photo Credit: Mehedi Hassan / Dhaka Tribune)