(we) laugh it off

we laugh it off

democratically

(even though

there was none

back there in 1976)

we laugh it off

myself and a folkie

a work colleague into

Dylan Baez and Jim Croce

June 1976 it was

circa the 16 and 17

a stay-away from work

(my first it was)

a manager fellow it was

(we are being genteel here

as he was harsher labelled)

suggesting we get

a police escort to work

we laugh it off

explaining to him

that they oversaw

apartheid and the like

(in the name of law and order

keeping us safe from the red peril

keeping us safe from the yellow peril

keeping us safe from the swart gevaar)

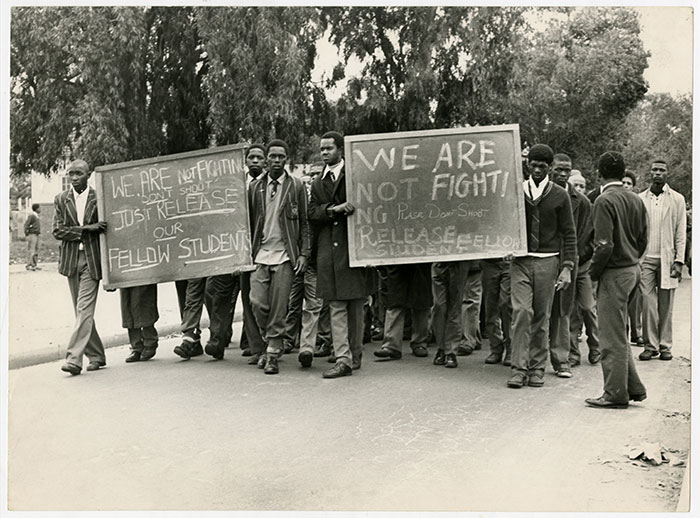

June 1976

the Soweto uprising

the Soweto student rebellion

(there are those who

called the event a riot)

many exiled in its wake

before and after

Youth does it matter

to you today

what this political holiday

was all about

Will it make tomorrow

any the better if you did

(Photo Credit: South African History Online)