HMP Peterborough is touted as a model private prison. It’s about five years old, run by Sodexo Justice Services. It houses, or contains, both men and women. The women are mostly remand prisoners, awaiting trial. Everyone is supposed to be short-term, low level, and generally available to `rehabilitation.’ As far as accounting goes, Peterborough brought to the United Kingdom, and in large degree to the world, “payment by results.” This means, the prison corporation is paid based on prisoner re-entry results. Some think Petersborough might be the way forward, the path out of the neoliberal prison forest. It’s not.

Keep the advertised fabulousness of Peterborough in mind as you ponder the story of Nadine Wright.

Nadine Wright is a woman living with disabilities and crises. Mental health illnesses. Heroin addiction. Her mother died in September, and there was no one to assist Nadine Wright. Meanwhile, the State repeatedly fails to make her benefits available to her. Wright did not receive her benefits in November. And so she was barely living, desperately poor, somewhere below hand-to-mouth.

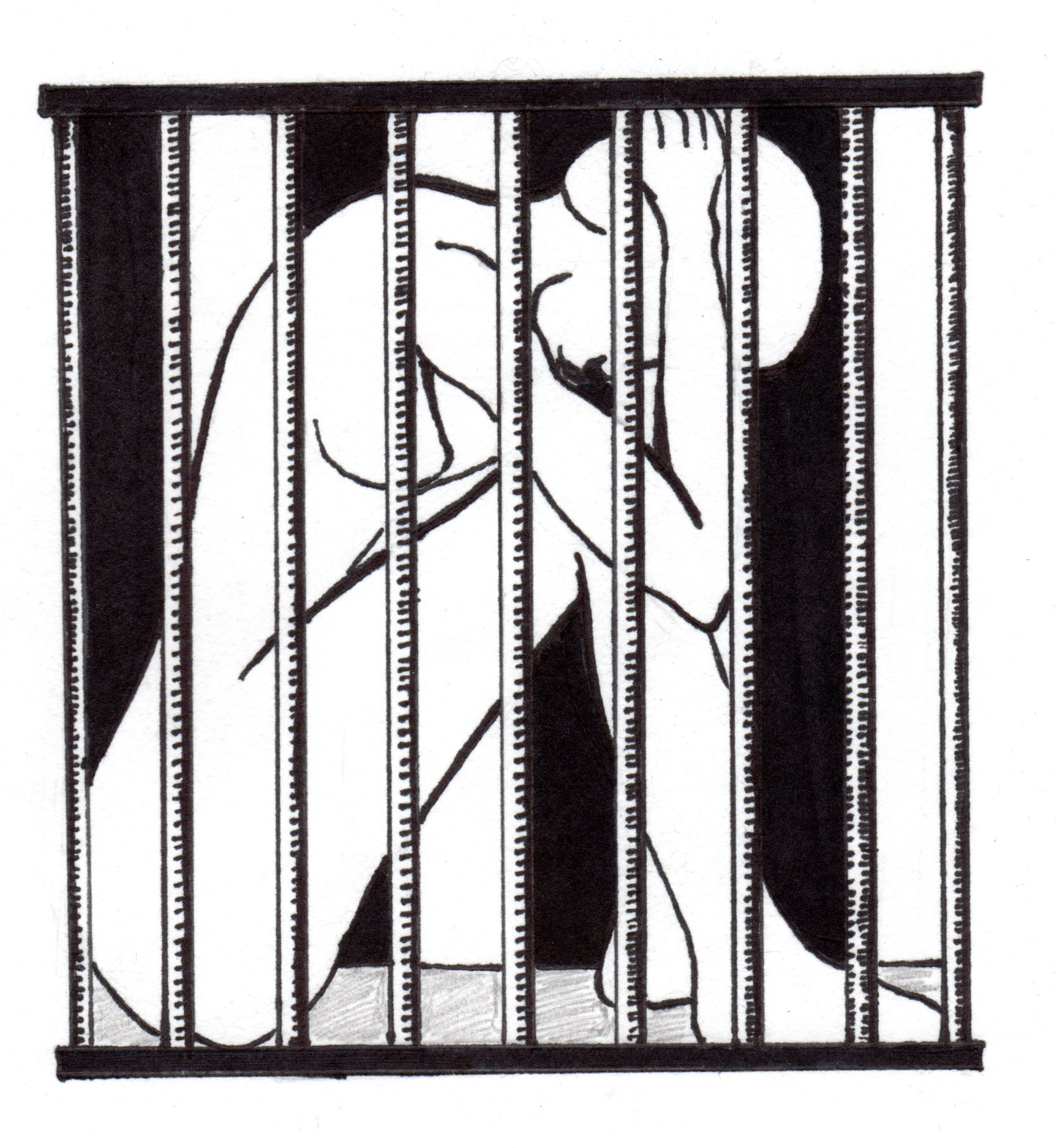

So, what’s a desperately poor woman to do? Nadine Wright stole some food. She was caught and arrested. She was sent to Peterborough. Nadine Wright was pregnant when she was arrested. While in her cell, she went into labor and suffered a miscarriage. A nurse was in attendance.

According to Nadine Wright’s attorney, the nurse then left the cell. She left the fetus in the cell. No one came to clean up the cell, and so Nadine Wright was left to clean up her own blood … by herself: “There was blood everywhere and she was made to clean it up. The baby was not removed from the cell. It was quite appalling. It was very traumatic. She only received health care three days later, after the governor intervened.”

Everyone failed Nadine Wright. Her probation officers and the entire probation system. The health providers. The prison staff. Sodexo. The State. Culture. A world in which prison is the answer to mental illness, to disability, to poverty, to trauma, to personal chaos and crisis, to women acting out, to pretty much everything. We all collude in that world. We all failed Nadine Wright, and we all continue to do so.

(Photo Credit: AFP / Getty / Independent)