Domestic workers fighting abuse and slave-like conditions need legal protection. While India’s labor ministry has begun preparations to provide social security for domestic workers, further protections for workers to demand better treatment from their employers and justice for abuse and mistreatment are still needed.

Recent instances of severe abuse of domestic workers in India include a 26-year-old domestic worker from Bangladesh who was held captive by her employer, based on false accusations that she had stolen from them. She had not been paid in two months. Elsewhere, a domestic worker was tortured and then murdered by her employers, a legislator and his wife.

Even if workers organize and rights have been won, the threat of retaliation from employers remains. For example, domestic workers in a complex in Mumbai went on strike for their underpayment by employers. The, employers conceded defeat and then months later fired the maids.

Domestic workers are vulnerable because of their lack of other employment choices. According to social activist Pratchi Talwar, “Many resort to domestic work because of decline in employment opportunities in the agriculture and manufacturing sectors.”

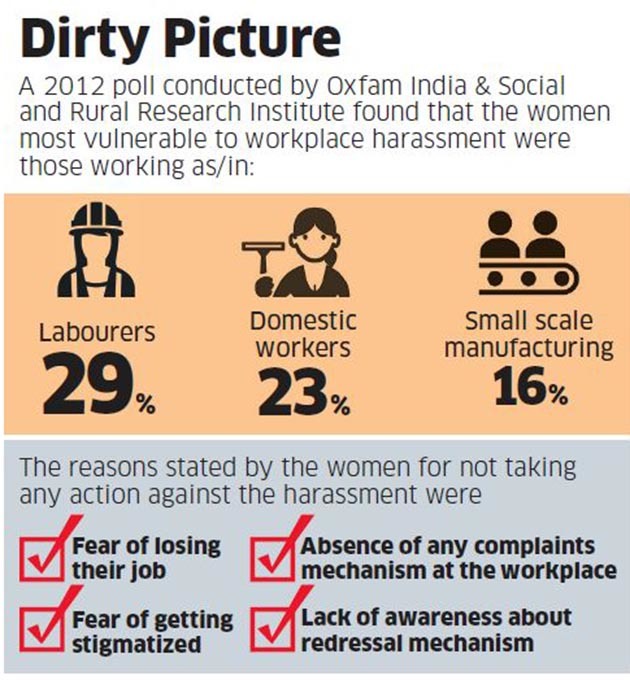

A poll in India conducted about workplace harassment highlights domestic workers’ vulnerability, claiming that these women do not retaliate from employment abuses because of the fear of losing their jobs, fear of being stigmatized, the absence of a means of filing complaints at the workplace, and the lack of awareness about redressal mechanism. These reasons, and the lack of means to address these problems, produce a continued pool of workers vulnerable to abuse and mistreatment form their employers.

India’s labor ministry has begun the process of addressing the concerns over the mistreatment of domestic workers by defining domestic workers as workers and providing the legal protection and social security that comes with the new legal status. The introduction of the policy is intended to “set up an institutional mechanism for social security coverage, fair terms of employment, addressing grievances and resolving disputes.”

According to Sonia Rani, project coordinator of the Self-employed Women’s Association, “These are just guidelines which are not legally enforceable. What happens when there is sexual abuse, withholding salaries and denying leave? Can the workers go to court? There also has to be a non-negotiable salary regime.’

Domestic workers continue to experience higher turnover rates and can be fired at will because there is no legal protection and no national law documenting domestic work as work, giving them all the protections of workers from such legal status. There are only two laws in India concerning domestic workers, the Unorganized Workers’ Social Security Act of 2008 and the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition, and Redressal) Act of 2013. Neither law recognizes domestic workers as having legal rights. Though India is a signatory to the International Labor Organization’s 189th convention on Domestic Workers, the country has not yet ratified it.

Policy shifts concerning domestic workers do not become concrete implemented law unless domestic workers are recognized as part of the labor force. Only when domestic work has been recognized as work can there be legal protections for women and girls employed as maids. Unions and organization have argued “that the mindset of regarding domestic workers must shift from a policy paradigm to one that focuses on workers’ rights. Only then, can domestic workers’ rights be defined and protected.” Until then, the actions are but a Band-Aid on a nationwide gaping wound.