Refugees have been in the news a lot lately. The strikes on Gaza offer one of the most prominent and horrifying examples happening right now. Zimbabweans fleeing the Mugabe regime, often classified as economically displaced, fall under the category of ¨refugee¨ in mainstream reporting. The U.S. occupation of Iraq has led to the displacement of millions of individuals and families, creating a massive refugee crises in which over 4 million have left their homes to find refuge in other parts of Iraq, Syria, Jordan, or other neighboring countries. Reporters cover humanitarian crises in Darfur, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Chad, Georgia . . . and the list continues. Given this broad naming of displaced individuals around the world as refugee, it would appear that all of these groups fall similarly under the category of refugee, although the historical and geopolitical contexts are markedly different.

This undifferentiated category of refugee seems to pop up, well, everywhere.

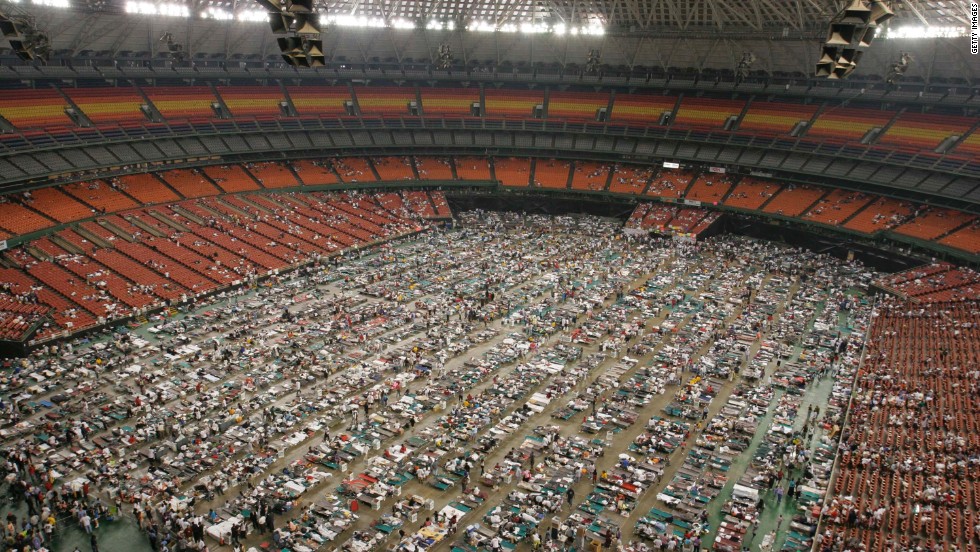

After reading a recent article in The Nation about New Orleans and the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, referenced in Dan Moshenberg´s recent post, I was caught off guard by A.C. Thompson´s mention of refugees. Recounting race-specific violence following the storm, Thompson says, ¨Facing an influx of refugees, the residents of Algiers Point could have pulled together food, water and medical supplies for the flood victims.¨ Refugee is just sort of slipped in there, no? Indeed, refugee became the contentious, yet popular, way of identifying displaced New Orleanians following the storm. However, while Thompson takes on the very important task of discussing forgetten histories of extreme white on black urban violence, he refers to the refugees rather nonchalantly. Information about where the refugees came from and why they might have fallen into the category of refugee remains curiously absent. Moreover, his portrayal of New Orleans is decidedly male, or at least male-normative, as all of the active players in the article are men. As we continue to remember Hurricane Katrina, we must ask the following question that few critics taken into consideration: where were/are New Orleanian women displaced by the storm, the majority of whom were poor and black? How did refugeeness following the storm differ along the lines of race, class, gender, location, age, and ability?

It is the frequent, unspecific, and gender-neutral use of the label refugee that concerns me. While the United Nations and individual nations maintain their respective legal definitions of refugee status, the name is used all too frequently in reporting about conflict and disaster to describe those who are victimized and desperately in need of aid, often perceived as coming from the largesse of the West. It seems that refugees, whether considered to be economic, political, religious, or otherwise, remain largely nameless, faceless, and desperately in need of help.

One of the most curious examples I have recently seen is the labeling of refugees fleeing Ciudad Juarez and moving to El Paso. According to Alfredo Corchado of the The Dallas Morning News, Senator Eliot Shapleigh says, “Just like the good people of Houston took in the refugees from New Orleans, El Pasoans will also help the refugees from Juárez.¨ Similar to Thompson´s portrayal of Algiers Point, all of the active players in the El Paso-Ciudad Juarez area are men. Given the use of label refugee to describe crises around the world and the increasingly high levels of femicide in Ciudad Juarez, this portrayal of ¨refugee¨ as narco-economic, male migrant is painfully shortsighted and disturbingly problematic.

In the majority of representations of mass displacement, the situations of women, especially women of color, remain obscured. These women, the third world `others´ lost in the traffic of disaster, conflict, and humanitarianism, exist outside of and below public intelligibility and political recognition. Given current reporting practices concerning refugees, especially those circulating in the U.S. public sphere, these feminized groups remain largely un-trackable and unspeakable.

(Photo Credit: CNN)