Archives for January 2013

Black Looks: 12th January, 2010

Domestic workers are women workers are workers. Period.

The International Labour Organization released a major study today, Domestic workers across the world: Global and regional statistics and the extent of legal protection. Though the report’s picture is largely what one might expect, it’s still worth engaging.

In 2010, at least 53 million women and men worked as domestic workers, up 19 million from the last count of 33.2 million people, in 1995. That’s almost a 60% increase in the size of the global domestic labor force. And remember, the numbers are always lowballed, so that the ILO suggest there could be as many as 100 million domestic workers.

Globally, universally, everywhere, domestic workers are overwhelmingly women. Which women might change from place to place, but they’re always women. Globally, 83% of domestic workers are women. Globally, 1 in every 13 women wage earners, or 7.5%, is a domestic worker. In Latin America, 26.6% of women workers are domestic workers. In the Middle East, 31.8% of women workers are domestic workers.

In the United States, 95% of domestic workers are women, of whom 54% are women of color. Latinas make up the largest group among the women of color domestic workers.

This means the status and state of domestic workers is part and parcel of the pursuit of gender equality. Addressing the inequities of domestic workers’ lives and situations is key to women’s emancipation … everywhere.

The United States gets something of a free pass in the report, but it shouldn’t. Here’s why. The report focuses on three areas of major concern: working time; minimum wages and in-kind payments; and maternity protection. Paid annual leave falls under the category of working time, and guess what? Of the 117 countries in the report, the United States is one of only three countries without a universal statutory minimum for paid annual leave. The other two are India and Pakistan.

When it comes to coverage of domestic workers’ control over their time, the United States is the only so-called developed country and the only country in the Americas that excludes live-in domestic workers from overtime protections.

The picture is worse when we turn to maternity leave. Among so-called developed countries, only the United States, Japan, and South Korea have no entitlement to maternity leave for domestic workers and no entitlement to maternity cash benefits. In the Americas, the United States is the only country that has neither maternity leave nor maternity cash benefits for domestic workers.

At the beginning of the 20th century, women were described as “being forced to become servants”. A hundred years later, they are described as “preferred by employers.” That’s the march of neoliberal progress. You weren’t forced; you were preferred. Otherwise, it’s been a century of exclusion of domestic workers from protective labor legislation.

It’s time to end that century. Domestic workers are under attack. They’re under attack because they are women. End the exclusion of domestic workers from national labor laws. Domestic workers are women workers are workers. Period.

(Photo Credit: ACelebrationofWomen.org)

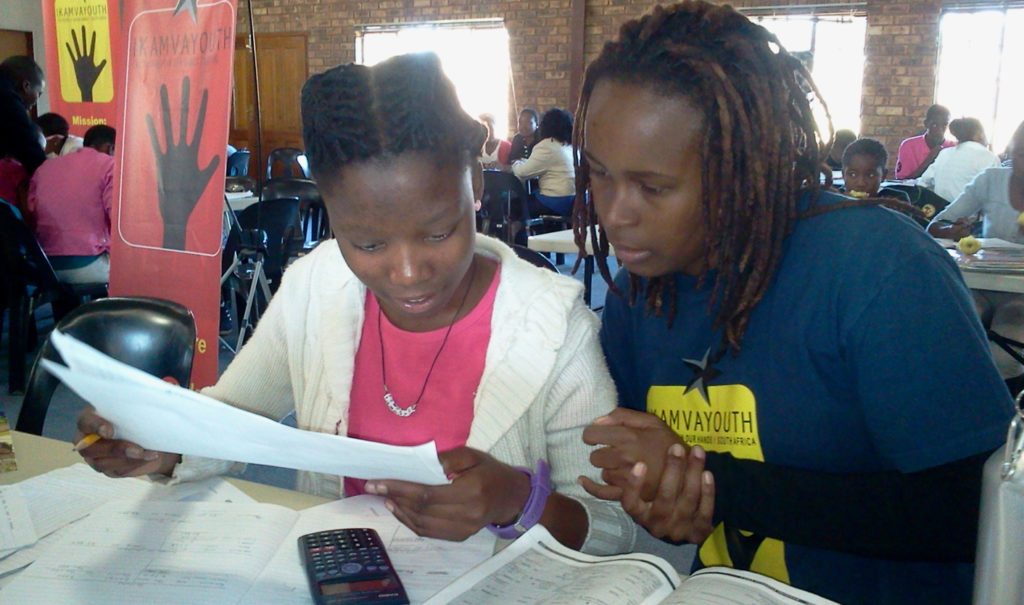

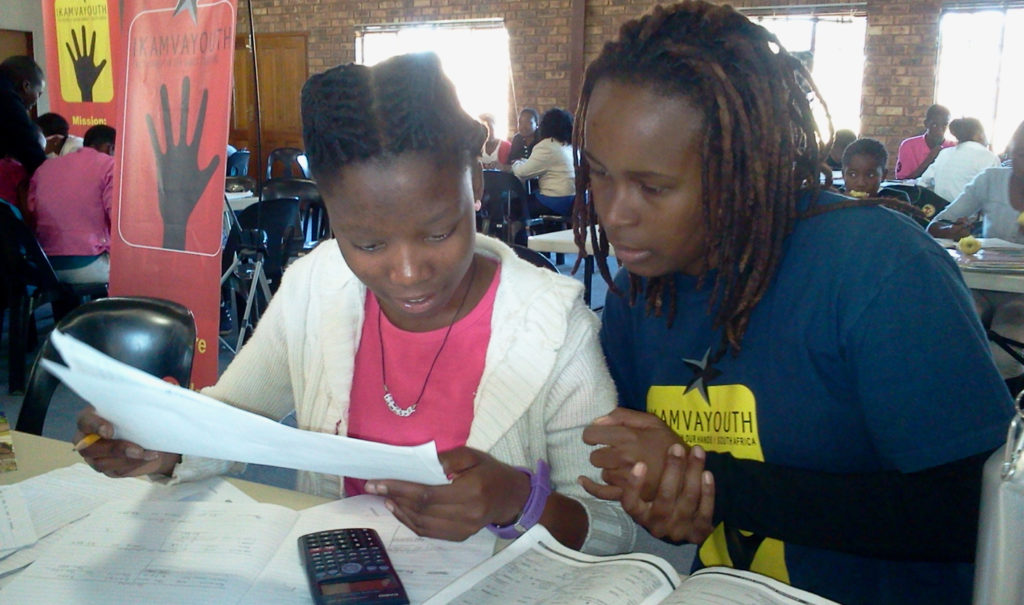

Ikamva means the future … is now!

In Xhosa, ikamva means the future.

Asanele Swelindawo. Ayathemba Njovane. Akhona Nokeva. Siyabulela Godwana. Rhondashein Ntebaleng Morake. Joy Olivier. Zamo Shongwe. Thabisile Seme. Khona Dlamini. Nyasha Mutasa. These are just some of the names of IkamvaYouth.

IkamvaYouth is a movement that began in Khayelitsha in 2003, in response to the tragedy of township education then … and in too many ways still is. Two researchers, Joy Olivier and Makhosi Gogwana, went to Gogwana’s old high school, only to find that it was impossibly worse than when he had graduated.

They decided to help matriculants graduate and prepare for either university or for full and gainful employment. They began small and, each year, grew. Each year, as well, their record of graduation and of successful entrance into university has grown by leaps and bounds. Today, IkamvaYouth has branches in Makhaza, Masiphumele, and Nyanga, all on the `outskirts’ of Cape Town, in the Western Cape; in Ebony Park and Ivory Park in Gauteng; and in Chesterville and Umlazi in KwaZulu-Natal. They are organizing two new branches this year, in Grahamstown, in the Eastern Cape, and one in Gauteng.

This year the Gauteng and KZN branches had 100% pass rates. 91% of the learners have qualified for university entrance. That’s impressive. But there’s more.

The literature on IkamvaYouth refers to it as a non-profit organization that draws on an ever-growing pool of volunteers. Others describe it as a successful tutoring and mentoring program or as a best-practices model grass-roots youth development organization. Much of the scholarly literature on IkamvaYouth focuses on social entrepreneurs, mathematics and science instruction, and the use of ICTs.

That’s all accurate, but it misses a key point: democracy. For Joy Olivier “IkamvaYouth drives social change… IkamvaYouth has a democratic youth-led structure.” The tutors are mentors, and the tutor-mentors are increasingly `Ikamvanites’, graduates of the program who return to keep the energy and the learning and the movement sustained.

Last year, IkamvaYouth made the 2012 WorldBlu List of Most Democratic Workplaces. IkamvaYouth is the first South African AND the first African organization to receive such recognition. Here’s what WorldBlu said: “IkamvaYouth empowers disadvantaged youth to lift themselves out of poverty into a university education or employment. IkamvaYouth practices the democratic principle of Fairness + Dignity by creating an environment in which each individual has an equal representative voice, regardless of rank or age. It is the “level of insight” on a particular issue that is valued above the position a person may hold. To uphold this value over a wide geographical spread, branches have online meetings, where a democratically-elected representative of each grade sits on the committee and is also involved in all decision-making. Minutes of meetings are sent to all participants and are available on Facebook groups for additional input. The youngest and newest members’ votes hold as much weight and value as their branch coordinators.”

Democracy matters. Democracy in education matters. IkamvaYouth is creating autonomous spaces of democratic action and nation building in South Africa. They are teaching the world that ikamva means the future … and the future is now!

(Photo Credit: Jon Pienaar/Daily Maverick)

The ticket to ride

The ticket to ride

I now have the ticket

to improve my life and

one day be able

to take care of my family

So says Asanele Swelindawo

an orphan who managed

to get three distinctions

in our much-maligned Matric

She is an Ikamva Youth member

a by-youth for-youth

volunteer-driven initiative

just up your street

The ticket to ride

at the end of it all

a stairway to heaven

folks would have it

(Zero to hero turnaround

out at Peak View High)

Though experts have it

that our matric ticket is one

loaded with mediocrity

(quality over quantity

the new post-apartheid

standard grade of life )

The ticket to ride

in the context of

our country gone

to the (pampered) dogs

(our girl-child illiterate

and barefoot and pregnant

out here in darkest Africa)

The future is in our hands

says Ikamva Youth

Is it in yours

An email missive tells it all: “IkamvaYouth learners from township schools achieve 100% pass rate with 91% eligible for tertiary education” (www.ikamvayouth.org); and the Argus “Zero to hero turnaround” and its Comment “Quality over quantity?” (Friday, Jan 4 2012).

(Photo Credit: Jon Pienaar / Daily Maverick)

Swazi women have always been on the move

Swazi women are on the move. Actually, Swazi women have always been on the move, organizing, opening spaces for women, opening spaces for democracy. Every year, the international media `discovers’ Swazi women on the move. But Swazi women know they have never been still and they have never been silent.

As Swazi feminist and labor organizer Cynthia Simelane explained recently, Swazi women have a longstanding tradition of organizing. Over 20 years ago, in 1990, women got together and started the fabulously named SWAGAA, Swaziland Action Group Against Abuse, an organization initially dedicated to addressing family violence and sexual abuse. They’re still going strong. In 2001, Thelma Dlamini, Siphiwe Hlope, Nonhlanhla Dlamini, Elina Hltatshwako, and Gugu Mbata, five middle-aged women living with AIDS, organized something variously called Swaziland Positive Living, Swazis for Positive Living, or Swaziland for Positive Living. Whatever its exact name, 12 years later, they’re still rocking, expanding, stretching, creating and representing. In 2009, Swazi women organized Swaziland Single Mothers Organization, which in the last year doubled its membership.

Between 2001 and 2009, Swaziland acceded to the Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, CEDAW, in 2004. In 2005, the King, Mswati III, “acceded” to a new Constitution, which contained some victories for Swazi women, including a Bill of Rights which enumerates the rights and freedom of women: the right to equal treatment and opportunity; the right to assistance from the State “to enhance the welfare of women to enable them to realize their full potential and advancement”; and the right to protection for women from being “compelled to undergo or uphold any custom to which she is in conscience opposed.”

While the Constitution is far from perfect (and what State document isn’t far from perfect anywhere?) and while its implementation has been spotty, at best, it’s not nothing. Ask Mary-Joyce Doo Aphane. She’s the woman who used the 2005 Constitution to sue for her rights to property under her own name. And, last year, she won her historic case. What’s in a name? Plenty, especially if the person is a woman. Ask Mary-Joyce Doo Aphane and all the women of Swaziland.

2011 saw the emergence of the Swaziland Young Women’s Network, a multi-focused organization committed to young women’s empowerment and to transforming not only the State but also everywhere and everyone in order to create autonomous spaces, once again, for women, in this instance for young women. And they’ve been kicking it ever since, from taking on public transportation’s sexual violence to creating vibrant events for young women artists to organizing last month’s mini-skirt march.

Swaziland is more than one corrupt monarch. Swaziland is hundreds of named and unnamed women’s groups, traditions, actions and movements, where women have always organized for the realization of democracy, not in some distant future, but now. The next time some article `discovers’ Swazi women are organizing, remember … Swazi women have always been on the move.

(Photo Credit: Swaziland Young Women’s Network)

Cry, cry, cry, set the women prisoners free

For the New Year, Zambia’s President Michael Sata released 59 women from prison. Of the 59 women, 43 are “inmates with children”, four are pregnant, and 12 are over 60 years old. As a consequence of President Sata’s move, 50 children, who were living in prison with their mothers, will see something like the light of day. The Zambian Human Rights Commission is pleased, as is Zambia’s Non-Governmental Organisation Coordinating Council. Both remind the President, as well, that now the State must attend to the “empowerment” of the 59 women. That includes economic, political, emotional, physical and spiritual well being.

In Uganda, members of civil society are calling on the State to “exempt women offenders with babies and expectant mothers, from long custodial sentences”. 161 children of women prisoners are currently guests of the Ugandan State. 43 of them are in Luzira Women’s Prison, aka Uganda’s Guantánamo. In March 2012, Luzira Women’s Prison at 357 percent capacity, and it’s only gotten worse since.

The situation for U.S. children of the incarcerated is equally horrible. In the U.S. the children don’t get sent to prison with their mothers. Instead, they are sent to “kiddie jail” … or they are left to fend for themselves at home, especially if the at-home parent is a single person, and more often than not in that case, a single mom. One study has shown that only a third of patrol officers modify their behavior or actions if a child is present. Of that third, 20% will treat the suspect differently if children are present, and only 10% will take special care to protect the children. That’s 10% of 30%. That’s 3%, in a country in which imprisonment is a national binge, and in which women are the fastest growing prison population.

And that “special care” can mean something like this: If an adult caregiver is arrested and there are no other adults around to care for a child, the child is taken first to the hospital, then to juvenile detention for processing, and then dropped off at a foster home. It’s a recipe for post-traumatic stress disorder.

The vast majority of incarcerated mothers lived with their children before going to prison. Almost half of incarcerated mothers are single heads of households. Most of their kids end up going to stay with grandparents. For those women prisoners who give birth to children while in prison, more often than not the children are immediately taken away, often forever.

And for women of color, and the children of women of color, it’s worse. For example, some judges give mothers longer sentences because “these women should have considered the impact on their children before committing a crime.” Women of color “bear the brunt” of that largesse.

Since 1991, the number of children under age 18 with a mother in prison more than doubled. In 2007, 1 in 15 Black children, 1 in 42 Latina/Latino children, and 1 in 111 White children had a parent in prison in 2007. Those are the ratios of racial justice and concern for children in the United States.

Make 2013 the year of the child. Set the women prisoners free, and, in so doing, set the children free.

(Video Credit: YouTube)