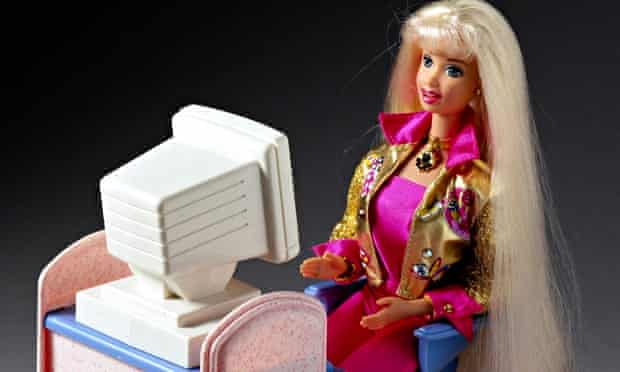

When Mattel announced that Barbie’s next career ensemble would position her as a tech entrepreneur, The Huffington Post offered a sympathetic piece detailing why the challenges of being a female entrepreneur would make this job Barbie’s “toughest yet.” While Mattel views this career choice as an opportunity for Barbie to “break through plastic ceilings” alongside actual female entrepreneurs (featured in a photo collage with Barbie in the center), the news of this doll—and the mainstream media’s response to it–immediately made me cringe.

The Huffington Post is absolutely right to call attention to gender wage gap, workplace discrimination, and underrepresentation of women in leadership positions. And with her hot pink corporate battle armor, “trendsetting” attitude, and upper class white background, Barbie is in a relatively advantageous position to face those challenges. However, the article glorifies female executives like Sheryl Sandberg as groundbreaking role models for Barbie and the enterprising young girls who play with her. This line of thinking is problematic.

By suggesting that women’s reluctance to more firmly advocate for themselves is the primary obstacle in achieving equality, Sandberg’s philosophy of Leaning In ignores external obstacles and systems of oppression that cannot be overcome with a positive attitude alone. Moreover, an increase in female CEOs is a solution reliant on capitalist systems in a society where high profile, high earning jobs are deemed the most valuable. This perspective overlooks the struggles of the many working class women who make up today’s globalized workforce.

Looking beyond Lean In, Entrepreneur Barbie (along with everyone who supports her) seems blind to the issues of gentrification and displacement that have faced Bay Area communities in the wake of Silicon Valley’s successes. For example, research from UC Berkeley shows that when companies like Google expand and use buses to transport their employees to and from work, they drive up the rents in the neighborhoods where those bus stops are located. This often means that the original residents can no longer afford to live there, or must struggle to maintain their standard of living, especially when landlords realize that they can make far more profits from new tech employees than from allowing their current tenants to remain.

In a political moment where communities of color in particular are being targeted and displaced from their homes, supporters of Entrepreneur Barbie are off the mark in hoping that the doll will “bring the next generation of girls with her on her journey to entrepreneurship.” This vision of trickle-down equality is dependent on maintaining the status quo for those already in positions of privilege and suggests that any upwardly mobile path is a good one, regardless of the cost to local communities. Barbie is not “uniquely equipped for this challenge because she’s a trendsetter;” she’s uniquely equipped because she is a marker of privileged whiteness and omnipresent corporate dominance. While Mattel may be aware of gender inequality in the workplace, Entrepreneur Barbie loses any redeeming value when she spreads ignorance of race-and-class-based struggles that no amount of Leaning In can ever solve.

(Photo Credit: Adam Hudson / Truthout)