Why do neoliberal so-called democratic nation-States continue to invest, and heavily, in the failed policies of mandatory minimum sentencing and tough-on-crime policies? Today we learn that women are at the center of the United States’ mandatory minimum sentencing `experiment’ and of Australia’s `tough on crime’ adventure.

According to family research scholar Joyce Arditti, “An examination of their family backgrounds and social environments suggests that mothers involved in the criminal justice system are perhaps the most vulnerable women in the United States.” These most vulnerable women then become the most extremely vulnerable women, `thanks’ to the theft of their social and legal parental rights.

According to Over-represented and overlooked: the crisis of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women’s growing over-imprisonment, a report released today by the Human Rights Law Centre and Change the Record, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are the fastest growing segment of the prison population. At the center of that largely unacknowledged growth is women’s vulnerability: “`Tough on crime’ approaches also tend to rely on stereotyped ideas of who offenders are, with little consideration of who else may be affected – the most vulnerable members of our community, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, are unfairly swept up into the criminal justice system.”

In 2014 22-year-old Ms. Dhu, died in custody in Western Australia. She was being held for unpaid parking fines. Ms. Dhu screamed of intense pains and begged for help. She was sent to hospital twice and returned, untreated, to the jail. On her third trip to the hospital, she died, in the emergency room, within 20 minutes. She never saw a doctor. Her grandmother says she “had broken ribs, bleeding on the lungs and was in excruciating pain.” Her death was deemed tragic, but not enough to change policy.

In July 2016, Ms. M, a young Wiradjuri woman and mother of four children, was walking home, when, a little after midnight, police picked her up, and threw her into a cell. At 6 am, Ms. M was “found dead.” In New South Wales, if an Aboriginal person is arrested, the police are supposed to use the Custody Notification Service, which immediately contacts the Aboriginal Legal Service (ALS). This system is a model. No Aboriginal person had died in police custody since 2000 … until Ms. M. But Ms. M was never arrested. She was thrown into the cell because she was said to be drunk. The police were “protecting” Ms. M, and so she died in their custody. Many, such as Gary Oliver of the ALS, believe that if the police had contacted them, “there may have been a different outcome. Fundamentally this is a process that has failed because a police officer has not followed a procedure.”

Today, former U.S. District Judge Nancy Gertner noted “that roughly 80 percent of the sentences she was obliged to impose were unjust, unfair and disproportionate. Mandatory penalties meant that she couldn’t individualize punishment for the first-time drug offender, or the addict, or the woman whose boyfriend coerced her into the drug trade.” Today, social justice advocates Vickie Roach described Australia’s tough on crime approach, “The criminal justice system … punishes Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women for actions that are the consequence of failed child removal and forced assimilation policies. If we are truly concerned about justice for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women however, we should be asking ourselves and our governments how we as a society have so badly failed these women.”

We invest in mandatory minimum sentencing and tough on crime policies because they succeed in intensifying the vulnerability of the most vulnerable: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in Australia, women of color in the United States. Vulnerability is big business. Increased vulnerability produces increased indebtedness. The more vulnerable and indebted women become, the more they are told to shoulder responsibility, individually and as a group, for all the wrongs that have been inflicted upon them, body and soul. Women die in protective custody, and it’s their fault. Mandatory minimum sentences are cruel and ineffective, especially for women, and that’s just fine. Tough on crime is destroying indigenous women and families, and that too is just fine. Our investments are doing just fine.

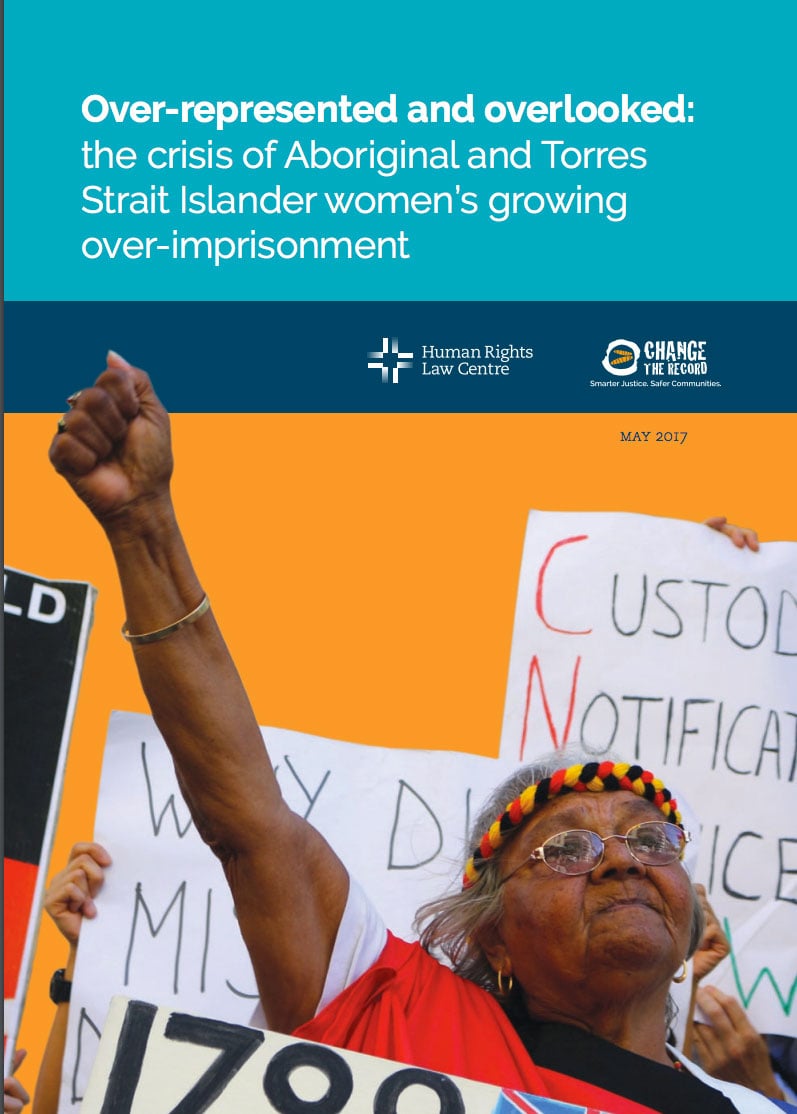

(Photo Credit: Echo)