On April 6, 2008, two police officers arrested 15-year-old Michell Joyce Radhuva and her mother and held them in custody overnight. Michell’s father came to the police station to secure their release, to no avail. Both were released the next day, without imposition of bail, and ultimately no charges were filed. But Michell and her mother knew the arrest was wrong, and so they immediately sued for wrongful arrest. They lost, repeatedly and at various levels, until last week, when the highest court in South Africa unanimously ruled that Michell’s rights, as a child, had been violated in the arrest and detention. The Court decided South Africa’s Constitution “seeks to insulate them [children] from the trauma of an arrest by demanding in peremptory terms that, even when a child has to be arrested, his or her best interests must be accorded paramount importance.” Amen to that.

On April 6, 2008, two police officers arrested 15-year-old Michell Joyce Radhuva and her mother and held them in custody overnight. Michell’s father came to the police station to secure their release, to no avail. Both were released the next day, without imposition of bail, and ultimately no charges were filed. But Michell and her mother knew the arrest was wrong, and so they immediately sued for wrongful arrest. They lost, repeatedly and at various levels, until last week, when the highest court in South Africa unanimously ruled that Michell’s rights, as a child, had been violated in the arrest and detention. The Court decided South Africa’s Constitution “seeks to insulate them [children] from the trauma of an arrest by demanding in peremptory terms that, even when a child has to be arrested, his or her best interests must be accorded paramount importance.” Amen to that.

The case is fairly straightforward. Two police officers came to the Raduva house to arrest Michell Joyce Raduva’s mother. Michell tried to intervene. The two were then arrested. The daughter was arrested for obstruction of justice. They were taken to the police station, booked, and held overnight. Whether the police knew Michell’s age at the time of arrest, by the time they arrived at the police station, they knew she was a minor. Not that that matters, since the police said, in court, that they would have arrested and detained her anyway, minor or not. To this, the Court responded, “What is more disconcerting is … a lack of knowledge and appreciation by the police officers of their constitutional obligation when arresting a child to consider her best interests as demanded by section 28(2). They demonstrate that the police officers did not care whether the applicant was a minor or not. Sergeant du Plessis said it expressly, that even if he knew that the applicant was a minor, he would still have arrested her. This is because he considers it to be his job to arrest. The fact that the arrestee is a minor would make no difference.”

According to Judge Lebotsang Bosielo, who handed down the Court’s decision, while the situation may be messy, the Constitution is clear: the best interest of the child is paramount. Period. In the balance of rights, the best interest of the child is paramount. In the actual existential moment, the best interest of the child is paramount. In this, the South African Constitution agrees with human decency and common sense, but, too often, not with State practice, not in South Africa nor the United States nor Australia nor England, where the State “considers it to be his job to arrest” and detain.

Judge Bosielo notes, “Under any circumstances an arrest is a traumatising event. Its impact and consequences on children might be long-lasting if not permanent … Detention has traumatic, brutalising, dehumanising and degrading effects on people … The applicant was seriously traumatised by this experience. Her detention has left her with serious psycho-emotional problems. Wounds that are still festering. These are the deleterious effects of incarceration against which the Constitution seeks to protect children.”

Being arrested is traumatic; being detained is traumatic … for anyone. For children, each can be catastrophic, and combined they can be life altering in the extreme. Michell Joyce Radhuva and her mother sued so that we might all know that, so that we might all remember that children are children are children. Children are children are children. Each child is a child and must be treated, and respected, as a child. That’s the law.

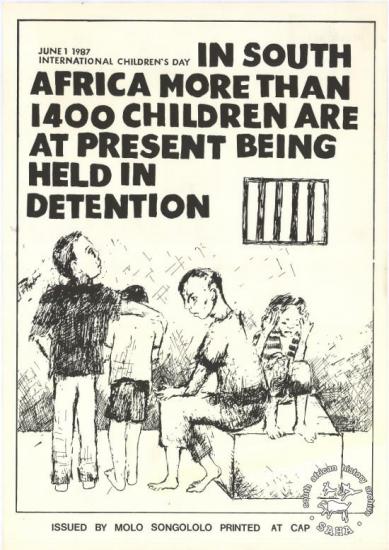

(Image Credit: South African History Online)