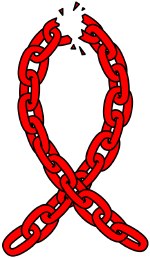

Women in shackles, women in prison, haunt accounts of prison.

In the U.S., some say it’s time to “Redeem the prison generation“: “The least popular constituency in America. People we’d rather forget. Last year, a record 1 in every 100 American adults was in prison. One in every 30 men aged 20 to 34. And among black males in that age group? One in 9. Why? Because America’s crime and punishment policies reflect an incoherent mix of motives: justice, retribution, vengeance, the illusion of expedience, the cruel bigotry of nonexistent expectations. And absent decent job training, counseling, and re-entry programs, the system only incites violence and invites recidivism. It’s past time to reconsider our approach to prisons, for practical reasons – and because it seriously undermines our effectiveness as a society and our moral authority with other nations. With just 5 percent of the world’s population, we cage almost a quarter of the world’s prisoners – a trend that has accelerated wildly since the 1970s. If the 2.3 million Americans now behind bars joined the 5 million on parole or probation to form a city of their own, you’d have a population nearly twice that of Los Angeles. Feeling safer yet? You shouldn’t.”

The prison generation. Not quite the Coke or Pepsi Generation, but then again, not quite not the Coke Generation. Are there any women in this account of the Prison Generation? Of course not.

But there are women in prison, some for their own `protection’, for their own `good’.

A woman is “jailed for her child’s own good?“: “A judge in Bangor, Maine — ignoring federal guidelines — has doubled the sentence of a Cameroonian woman charged with possession of false immigration documents. Was there something extra-heinous about the nature of her crime? No. Despite protests from the defense and the prosecution, U.S. District Judge John Woodcock sentenced Quinta Layin Tuleh, 28, to 238 days in prison — twice her time served, which would be standard sentencing practice here — because she is HIV-positive and pregnant. Her release date, in fact, is her due date. From today’s Bangor Daily News: “Woodcock said the sentence would ensure that Tuleh’s baby, due Aug. 29, has a good chance of being born free of the AIDS virus.”

“Woodcock reportedly informed Tuleh at her May 14 sentencing that he intended the longer term not as punishment for her, but as protection for her unborn child. He said that the defendant was more likely to receive medical treatment and follow a drug regimen in federal prison than out on her own or in the custody of immigration officials,” says the News, adding that his decision, he said, was based entirely on her HIV status; if she were pregnant but HIV-negative, he’d have left it at time served. (Some drug regimens have proven effective at preventing HIV transmission from mother to fetus.)….

“”My obligation is to protect the public from further crimes of the defendant,” Woodcock stated, “and that public, it seems to me at this point, should likely include that child she’s carrying. I don’t think that the transfer of HIV to an unborn child is a crime technically under the law, but it is as direct and as likely as an ongoing assault. If I were to know conclusively that upon release from imprisonment a defendant was going to assault another person, I would act in a fashion to prevent that, and similar to an assault, causing grievous injury to a wholly innocent person. And so I think I have the obligation to do what I can to protect that person, when that person is born, from permanent and ongoing harm.”

“If Tuleh’s child is indeed born here, he or she would be a U.S. citizen. But an immigration expert told the News that an infant would most likely be deported along with the mother.”

Tuleh is not in shackles, and yet she is. If her fetus comes to term, if the child is born, in the United States, that person will and will not be a U.S. citizen, and it, not he and not she but it, will be deported. The Prison Generation … a new line of U.S. exports. The Prison Generation, haunted by the women, and especially the women of color, who never get a mention.

(Image Credit: thebody.com / Project UNSHACKLE)