According to a recent study, as described in a post here last month, in the United States, being a person is tricky business if you are pregnant, poor, or a woman of color. That study responds to two sets of interrelated events: [1] the effort to pass laws that give a fetus the constitutional right of a person, thus far passed in 38 states; and [2] the increased number of arrests and incarceration of pregnant women.

The study raises many questions, ranging from the conceptualization of protection, including medical care, based on the socioeconomic status of the pregnant woman, to the concept of fetus personhood. Fetus personhood was embedded in the Roe v Wade decision in its discussion of a woman’s right to terminate her pregnancy as “not absolute, and … subject to some limitations…. A State may properly assert important interests in safeguarding health, in maintaining medical standards, and in protecting potential life.”

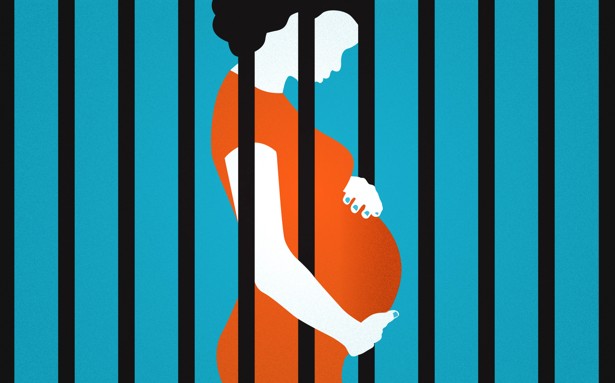

Pregnant women have been incarcerated with greater frequency because of the establishment of a process that renders them available and appropriate to incarceration. The study identifies that process through the records and examination of the incarceration of pregnant women in the United States between 1973 and 2005. In every case the bases of arrest was the protection of the personhood of the fetus.

Being-pregnant, then, has become being-powerless. At one level, this is not new. In Beggars and Choosers, Rickie Solinger recounts how officials used White pregnant teenagers to fuel the adoption business: “Beginning in the late 1940s, community and government authorities together developed a raft of strategies some quite coercive, to press white unwed mothers to relinquish their babies to deserving couples” (70). Those teenagers were presented as “mentally disturbed” because they failed to have a husband to protect them, “a proof of neurosis,” making them potential bad mothers. The same authorities singled out and removed unwed Black teenage mothers from any public assistance, intensifying their already precarious situation.

In both cases the personhood of the young woman was reduced to being a carrier in which the state had a prevailing interest of control and protection. In this historical context, the Roe v Wade decision allowed the same ambivalence to be developed concerning the personhood of all women, with the invisible hand of the state ready to take over a woman’s right to control her body.

The study emphasizes the responsibility of the perverse effects of this lack of clarity of the woman’s existence as a person with regard to women’s versus fetus’ personhood. These effects created an insidious web of laws, which have led to the mounting incarceration of pregnant women. The fact that 38 states passed feticide or similar laws that have justified the arrest of pregnant women is no accident.

As we saw with Aaron Swartz’s suicide prompted by the violence of the American justice system, no campaign with celebrities and intellectual was organized to defend an individual who tried to defend our rights. In the case of both incarcerated pregnant women and Aaron Swartz, the outcry is limited and will probably remain so, thanks to the combined power of the State and a Civil Society that bends to corporate needs and wishes. Every day in this country, women are imprisoned because they are less important, they have less being-in-the-world, than something called the protection of “potential life.” Where is the outrage?

(Image Credit: The Atlantic / Lauren Giardano)