The ticket to ride

I now have the ticket

to improve my life and

one day be able

to take care of my family

So says Asanele Swelindawo

an orphan who managed

to get three distinctions

in our much-maligned Matric

She is an Ikamva Youth member

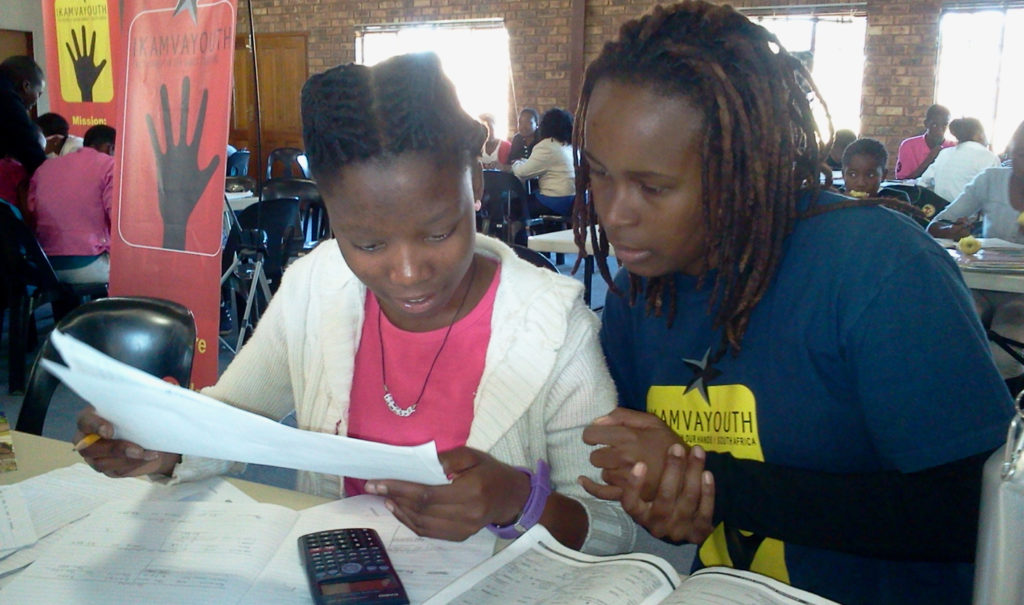

a by-youth for-youth

volunteer-driven initiative

just up your street

The ticket to ride

at the end of it all

a stairway to heaven

folks would have it

(Zero to hero turnaround

out at Peak View High)

Though experts have it

that our matric ticket is one

loaded with mediocrity

(quality over quantity

the new post-apartheid

standard grade of life )

The ticket to ride

in the context of

our country gone

to the (pampered) dogs

(our girl-child illiterate

and barefoot and pregnant

out here in darkest Africa)

The future is in our hands

says Ikamva Youth

Is it in yours

An email missive tells it all: “IkamvaYouth learners from township schools achieve 100% pass rate with 91% eligible for tertiary education” (www.ikamvayouth.org); and the Argus “Zero to hero turnaround” and its Comment “Quality over quantity?” (Friday, Jan 4 2012).

(Photo Credit: Jon Pienaar / Daily Maverick)