Brenda Rhode and the Young Authors’ Club

It’s in the genes

It’s in the genes

we hear of youngsters

crazy about books

and reading too

It’s in the genes

and not their jeans

I must add as I have

my mother’s English

tea-drinking habits

Crazy about books

and reading too

like their parents

and their parents before

(might we lionize them

rather than those

who tyrannized nations

colonized people

and played apartheid sport)

It’s in the genes

and not their jeans

or trousers, if anyone

still uses that word

(Did they honour

World Read Aloud Day

by reading up a tree)

Crazy about books

and not shiny objects

and brand labels

It’s in the genes

crazy about books

and reading too

Aren’t you

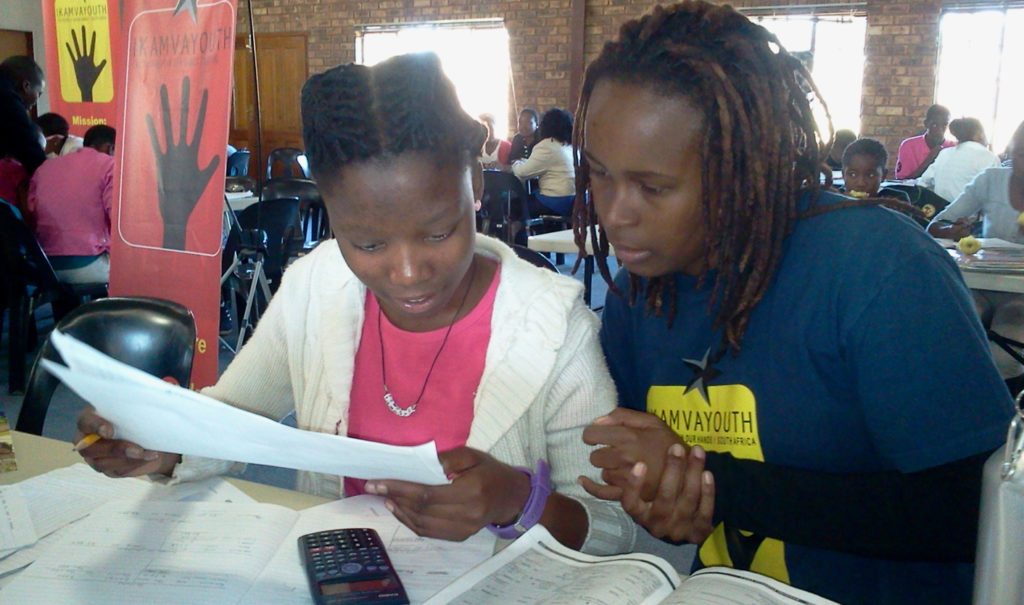

A social media tale (or “chronicle”) courtesy of Brenda Rhode – she of Young Authors Club fame and fortune – gets my chromosomes going, sometime Tuesday 17 April 2013.

David Kapp

(Photo Credit: Young Authors’ Club / Facebook)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/2YF4IU4PFBEJPH5ROBEQTWMC5U)