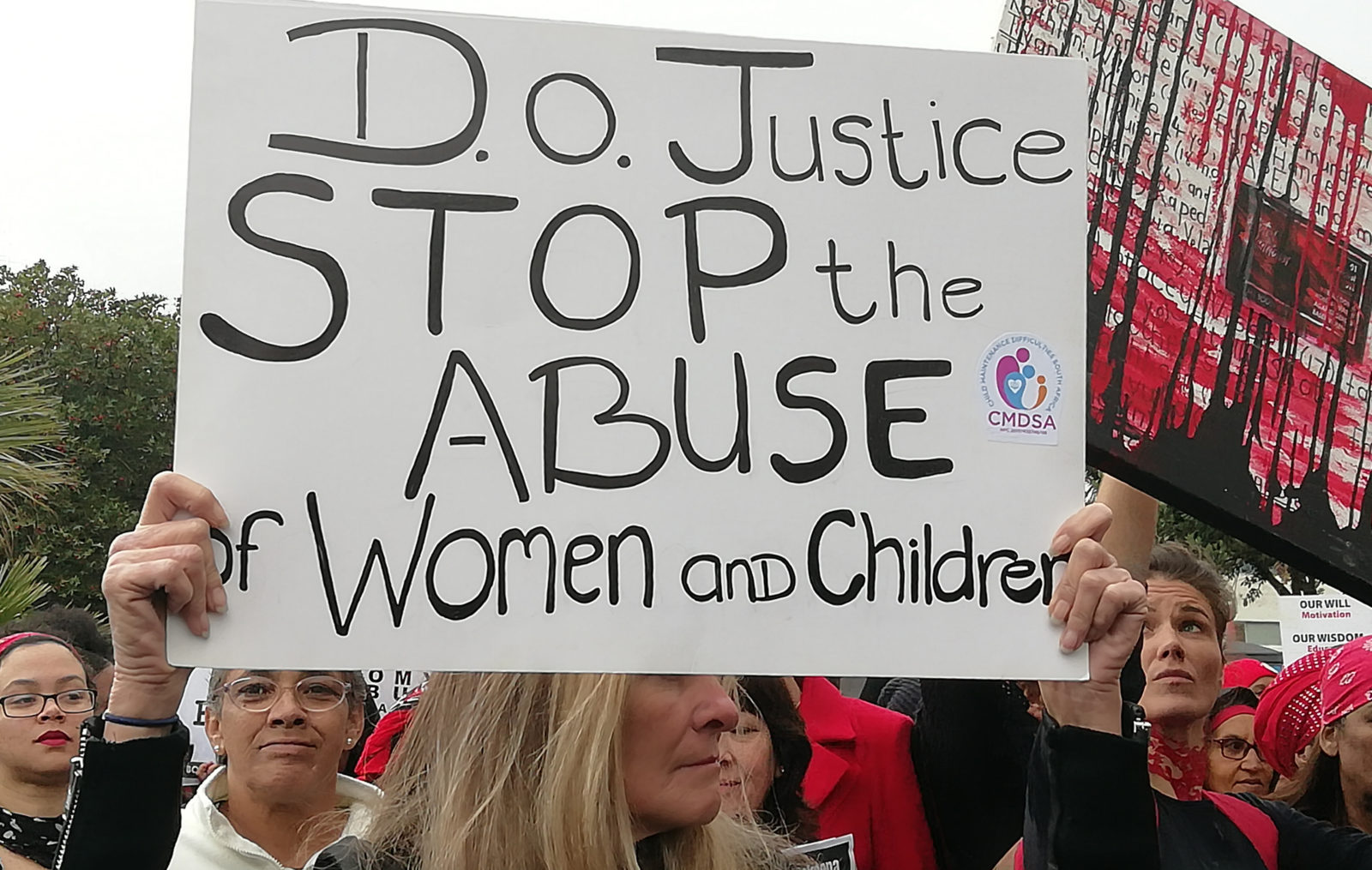

So it’s Women’s Day in South Africa, and we went down to hear a friend of mine speak at a local event. It was faintly cheering: we got to sing Malibongwe, which is the one struggle song white people can actually sing. There was clapping, and a bit of praying, which went down well. We then settled in for a desperately dull morning, in which we all bemoaned the general state of women in South Africa, and the wave, torrent, oh all right, tsunami of violence that is unleashed on us every day.

Yawn.

Yes, we agreed, we are dying. In fact, more than we can count, because the statistics are so unhelpful, given the level of underreporting of rape. Yes, we agreed, it’s very bad. We must fight patriarchy. We nodded our heads. Yes, indeed we must.

And speaker after speaker belaboured this, as though we had just woken up, and decided to talk about this for the first time. Lordy, it was dull. Except for one moment, one interesting electrifying moment. A woman academic, and feminist, and part of the national Commission on Gender Equality said, in one of the tightest, most frustrated voices I have ever heard, ‘We should go and stop the traffic. We should go to the nearest national road, and protest, and stop the traffic.”

And the hall of women groaned and rumbled, and it seemed like for a moment, for a flicker of time, that they would rise up as one and march, limping and dancing, out into the streets and burn things, and break things, and generally get seriously out of hand. It seemed to me that this wave of the possible reached her across the stage and she caught herself, aware of her responsibilities, and said, ‘No, not that I am suggesting violence or anything. But we must do something.’

The hall settled back down. We went to lunch. But that thought spoken aloud is still ringing in my ears.

(Photo Credit: http://theinspirationroom.com/daily/)