Mix it

Mix it

your metaphors

images and symbols

professors of doom

demoralizing our people

(whosoever our people

might be this time round

matric results under scrutiny

on the horizon)

Mix it

like anti-majoritarian

liberal critics

(a dangerous elitism)

(making hay

on a scrabble board

with big words)

So says the guardians

of our selves

keepers of the keys

to the democratic project

(the democratic project

led astray by mixing it

some folks might say)

Mix it

twitter and tweet

even twerk your way

to the dustbins of history

Pass one pass all

(suffer our born-frees)

recite from your songbook

peddle your election-wares

in Mandela’s name

Mix your metaphors

and I’ll blend mine

Our red-blooded spokespersons counsel…. “all our people not to be demoralised by professors of doom and anti-majoritarian critics” (“Serious challenges face education system despite matric pass rate rising”, Cape Times, January 8 2014); and “Dangerous elitism a worry, and no dustbins should await failed Grade 12s” (Cape Times, January 10 2014).

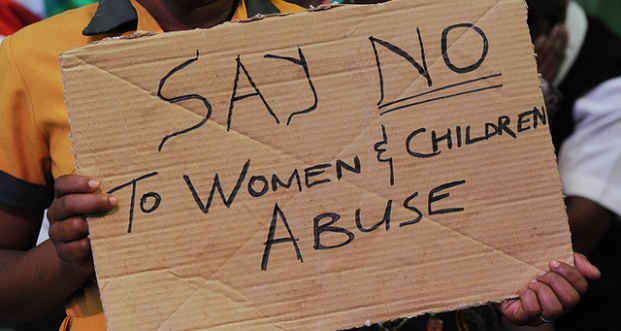

(Photo Credit: eNCA / Bafana Nzimande)