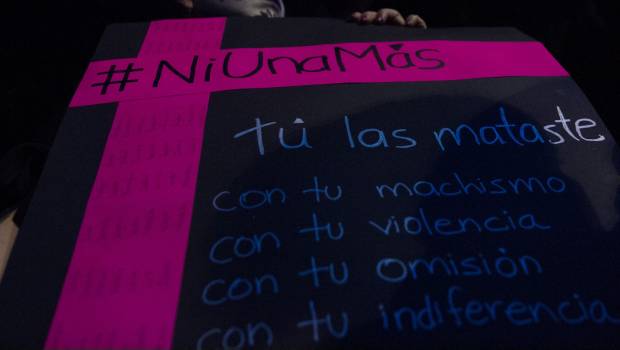

“In 1993, a group of women shocked Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, with the news that dozens of girls and women had been murdered and dumped, like garbage, around the city during the year. As the numbers of murders grew over the years, and as the police forces proved unable and unwilling to find the perpetrators, the protestors became activists. They called the violence and consequent impunity for the crimes `femicide,’ and they demanded that the Mexican government, at the local, state, and federal levels, stop the violence and prosecute the murderers.”

In 1993, the murder of women, and the refusal of the State, in this instance the Mexican state, to do anything, was shocking. In an interview today, Luis Raúl González Pérez, President of Mexico’s National Commission for Human Rights, said that, across Latin America, 12 women are murdered every day. Seven women are killed every day in Mexico. In Mexico, this is called feminicidio. In English, it’s both femicide and feminicide. Whatever it’s called, it’s an atrocity, one that’s been created by successive Mexican governments, governments north and south, east and west of Mexico, multinational corporations, and more. Mexican femicide is the nation’s, and the world’s, cost of doing business. That’s why the hotspots of femicide in Mexico have moved from the southern border to the northern. Ever increasing mounds of women’s cadavers is not even collateral damage in the national, regional and global development scheme, and those mounds are piling up at an ever-increasing rate.

A recent report on household relations, from the National Institute for Statistics and Geography, suggests that in Mexico 7 out of every 10 women has experienced violence, most of which is sexual and emotional. Ten areas exceed the national average. In Mexico City, for example, eight of ten women have suffered violence.

Right now, 12 areas in Mexico have been issued a “femicide alert” by the Commission. Another five been under the alert for almost six months. When these alerts are issued, the locale often sees it as a hassle and an embarrassment. As González Pérez explained, “Local governments must see that this alert is a tool that does not seek to harm, but to contribute to the solution of the problem. [Some consider it a political coup] because it is misunderstood. It feels like it’s reproaching them for the past, but it’s actually a proposal to move towards the future.” In what world do governments see femicide as a misplaced garbage dump, as bad for business, and nothing more? In our world.

Since that day in 1993, women have been protesting, organizing, militating against femicide. Mexican women have reached across borders and across oceans for support and for models of anti-femicide activism and policy. Since January 2016, Maria Salguero, a geophysical engineer, has designed and maintained an interactive femicide map. Guadalupe García Álvarez, a member of the Mazahua indigenous nation, suffered violence at home and then, at the age of 13, was sent to Mexico City to work as a maid. She decided enough was enough, and left. She went to university, completed her studies, and then returned home, where she founded, MULYD, Mujeres Lucha y Derechos Para Todas. Women’s Struggle and Rights for All (Women and Girls). Poets, such as Mijail Lamas, have invented new kinds of poetry, documentary poetry, to do more than “draw attention” to femicide and to violence against women. Lamas, and other poets, are insisting that the assault on women is an assault on language, on communication, on the soul and spirit of each and every human being, and not only in Mexico.

Every day, seven women in Mexico are murdered. That arithmetic is described as a crisis. It is. The crisis is violence, the violence committed by men in relationships, by men in corporations and investment agencies and banks, and by men in charge of governments, and not only the government of Mexico. Where is the global outrage at a contemporary witch hunt that threatens, as they always have, every woman?

(Photo credit: SDP Noticias / Claroscuro)