Flamingos on the Black River

A journalist sent me an email recently, asking for comment on the Cape water crisis. His email was titled *Will Cape Town survive the deadliest water crisis?* Here’s my response.

Thanks for writing. I worry about your email headline though: this is not “the deadliest” water crisis and yes of course the city can survive it, if the narrative we work with is productive. Making it about “survival” (presumably v extinction) and “the deadliest” generates scripts for individual survivalism — and therefore that kind of story becomes self-fulfilling. My PhD was on journalism and narratives of crisis and conflict in KwaZulu-Natal in the 1990s. I feel very strongly about the role of the media in generating responsive, responsible stories. See for example Ben Okri’s incredible booklet on stories and storytelling — “A Way Of Being Free” — where he sets out in pithy and quotable numbered phrases how we become the stories we tell ourselves. So you have a role too, in facilitating the kind of narrative that can enable collective action.

That is not, of course, to punt “sunshine journalism” or pretend that all is well, or no criticism is allowed. Far from it. This is a terrible situation, that’s arisen not only from some terrible decisions but also from a lifestyle that is the ideal of city living. Like any other terrible situation this can bring the best out of us (if we learn how to work together and transform how we live as households and as a city — a feminist ethic of care) and the worst (if we work on “my-household-uber-alles” survivalism — the patriarchal principle).

The greatest failing of the political management of the crisis so far has been the failure of leadership to offer a narrative that encourages people to pull together. But perhaps — if I think as a social scientist — that failure is not just an oversight but symptomatic of the broader problem: and that is the idea that “experts” will solve this. There are two problems with this:

* like weather forecasting in a time of climate crisis, expertise discovers its limits when the predictables are no longer predictable.

* Expertise that is based on the patriarchal and militaristic “command and control” is based on the idea that expertise has no limits.

Spot the loop?

As a feminist scholar who reads a lot of decolonial thinkers’ work, I think there is something very important to think about here: that both our modes of “I know everything” expertise, and modes of collective organising (command and control) — reach their limits in a time of crisis.

So experts and decision-makers have two choices: either carry on pretending to have complete expertise and have everyone but themselves see the hubris of that, or work with people to say — “look: we were totally wrong to assume that rainfall patterns would stay high. We’ve made choices in those years to spend funds on other pressing priorities (this is what they were; we will put together a commission of enquiry to try to learn what went wrong with water sciences, and /or the communications between our water expertise and decision-making.) But right now we have a crisis to solve — and we can either fight with one another, or address this using what we have learned in the past about collective action. So let’s create a water crisis committee with all public sectors involved, and create street committees on every street, and work out how we can partner together poor and rich areas so we can ensure we can get through the next 180 days together.”

The key is to move from “command and control” approaches to implementing expertise to an ethics of care, of relationships – because relationships and collective action are the only way we can do this.

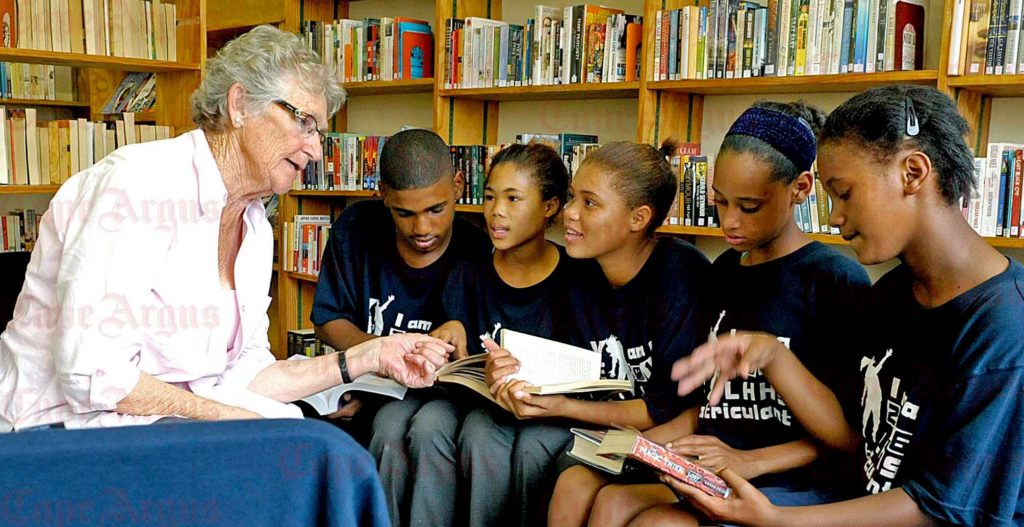

South Africa in general, and Cape Town in particular, have a strong history of collective action in opposing apartheid. We need to reclaim that, and bring the best of UDF-style leadership into this. “Each one teach one”; street committees to ensure care for those on your street, and partnerships to care for sectors far away. For example, middle class and elite and working-class street committees could work together to put up a number of water filters and rain water tanks at poorer schools, or sponsor a couple of roller barrels. Or work with NGOs like Habitat for Humanity to facilitate work parties to construct compost toilets — which are NOT expensive to put up, but need to be done properly and managed well. Or churches or Rotary style organisations or specific districts could also offer a truck or sponsor truck hire for people living in areas without transport to fetch water. And yes, there will be conflicts — but if you remember the Peace Committee structures of the 1990s there were teams available to help resolve conflicts.

South Africans are incredibly divided and this kind of crisis will either force the faultlines wide open — an earthquake-style catastrophe — or offer an opportunity to step over the city’s dividing lines and start to fill the cracks.

How you do that is not via command and control relationships, but by drawing the best out of people. Encouraging relationships of care: knowing that what matters to one, matters to all. The labour power available through mass mobilisation of generosity based on care for the bigger picture is what gets you through tough days. While it is going to be difficult to persuade the racist, nationalistic, individualistic and patriarchal among us (and often inside us) to do this, the situation is dire: either we work together as a city, based on care and noticing needs, or we destroy our possibility of being a collective, which is what a city is. The question everyone has to think about is what does it mean to be a collective, in this situation? In that way we rediscover politics — and more specifically, an ecological politics: that we all depend on everyone’s wellbeing; that everyone depends on our capacity to create a workable ecology for homes and services and businesses. What is normally scoffed at as “utopian” in the “strongest individuals survive” mentality promoted by neoliberalism, is now a basic and necessary home truth. The democratic social contract only works if you create a functioning ecology. The city’s ecology has broken down because of low rainfall: human collective effort is now needed to supply what “ecosystem services” have done for free.

You asked what I meant about seeing this crisis as an opportunity to build a greener and more climate resilient city. The rise of cities since the 1960s has been extraordinary, and cities are only possible because of sewage management and bulk water, bulk energy and bulk food supply, and waste removal. But the ecological costs of bulk supply are enormous. Cities are extraordinarily wasteful infrastructures because they are built on the idea of bulk supply only, removing the responsibility of all to live ecologically. Most urban design gives barely a thought to water or energy. So whole new developments go in as if they are alien spaceships and have nothing to do with the ecologies that sustain them. Hard surfacing means water runs off very fast, as stormwater, and doesn’t seep into the soil. Result: no aquifer recharge; flooding; lowering of water table; drier soils; loss of large trees; higher temperatures on streets; more aircon, more fossil fuels, greater climate change. Simple water-wise solutions would change this. So: this crisis makes it evident that water-sensitive urban design must become mandatory for EVERY new development.

I think it is entirely appropriate to look at Cape Town (and Port Elizabeth, for that matter — also facing a day zero) as an example of an evolutionary limit of a city based on that kind of “eco-thoughtless” design. At some point the system collapses in on itself, whether through poor planning (in one large city) or through changed climate (from so many large cities). But consider rainfall in relation to roof area in Cape Town. If every rooftop was harvesting rainwater, we would be well on the way to saving the water that falls locally — and it is a lot — we would be storing local downpours as well as the water that the faraway dams collect. The city can and should be looking at localised water solutions, at household level. There should be a subsidy system for water tanks and guttering into them. That would build more climate change resilience for the coming years.

Consider sewage. Cape Town has a massive problem with sewage going out to sea. We could be recycling about 50% of the water from sewage, I’m told by engineers, and ensuring that pharmaceuticals and organic pollutants are removed. Again, this will lead to greater climate resilience. Compost toilets are also very useful — I’m installing one in my home — but there too, I worry about persistent organic pollutants getting into soil and the water table or aquifers, so I’m not convinced these are a long term solution for a major city on major medications, and using the kind of toxic cleaning products that supermarkets push.

There’s another whole discussion there: Why do we clean our houses with toxins and call them clean? Surely we need to rethink “clean” beyond “shiny” to consider the health of the whole household — and its ecology. The word “ecology” comes from the Greek word “ekos” (oikos, if you use the correct spelling). “Ekos” means HOUSEHOLD. It is also the root word of “economy” and “ecumene”. This ecological crisis in which we find ourselves has come about because we have split ecology from economy, thinking of economy only as finance, not natural flows, growths and cycles. And we have split ecology and economy from ecumene, or society: forgetting that the three depend on each other, and come together in how we live, how we make our homes.

Then let’s look at the city’s rivers. The Black River, the Liesbeeck, the Eerste, the Kuils, the Keyser — these should be clean, and should be sources of water that we could use in this crisis. It is scandalous that they flow every day but that their waters are so filthy the city can’t even consider using them for drinking water. It is true that the flamingoes are back on the Black River, and that is the accomplishment of a team of under-resourced fresh water ecologists who’ve done extraordinary things. But the rivers are still terrible. That needs to change. We need to reclaim our relationships with rivers, and care for them and their water like we care for the health of our own arteries. Collective clean ups of the river are possible. They flow through communities rich and poor. River clean ups can be vital spaces of collective care and attention across race and class divides.

Spring water: that the city is finally re-piping some of its springs into dams is brilliant. Bravo. A small but vital step towards climate resilience.

The above infrastructural interventions span short and long term. The point is that through this crisis, the political will towards ecological solutions is being rediscovered. We are discovering that the city is not a spaceship. It is part of planet earth, and we need a politics that works with local planetary processes — which is what local ecologies are. In this, we can, if we choose, recognise the limits of individualism, and rediscover the power of collective action. In an era that has come to be defined by anti-politics, reclaiming this kind of collective, public-minded, ecological politics is what will make the biggest difference. Philosopher of science Isabelle Stengers has written a great deal about science and politics in the coming climate crisis. The translation of the title of one her recent books is “In times of crisis, resist the impulse to barbarism.”

Can Cape Town act collectively to generate a new eco-politics? That’s the issue.

(Photo Credit: UCT News)