Pennsylvania has a special treatment for those living with severe mental illness: torture. If someone who’s been arrested cannot assist in his or her own defense, the judge orders competency restoration treatment. If the defendant’s competency is restored, the case goes forward. If it is not restored, the case is dismissed and the person either is released or “civilly committed.” That’s what is supposed to happen. In Pennsylvania, there’s a third way, a purgatory of uncivil commitments. In Pennsylvania, people sit in county jails, more often than not in solitary, for months and years, waiting for a bed. In recent years, at least two people have died while waiting. They may have been the lucky ones.

Last week, the ACLU of Pennsylvania filed suit on behalf of eleven plaintiffs, whom they describe as part of “hundreds of people with severe mental illness who have been languishing in Pennsylvania’s county jails.” The lead plaintiff, J.H., is a homeless African-American man in his late 50s from Philadelphia who suffers from schizophrenia. J.H. was arrested for having stolen three Peppermint Pattie candies. For that crime, he has been sitting in the Philadelphia Detention Center for over 340 days, waiting for treatment. What becomes a dream deferred? “J.H.’s mental state has visibly deteriorated over the past eleven months in jail. Prior to his most recent detention, J.H. never displayed hostility, was relatively engaged during conversations, and was willing and able to answer simple questions. Now, he is visibly agitated, hostile, and unable or unwilling to engage in conversation.” The rest is silence.

Federal courts have decided that any delay longer than seven days between a court’s commitment order and hospitalization for treatment is unconstitutional. In Philadelphia, the average wait is 397 days. From January to September 2015, 23 individuals arrested in Philadelphia entered into restoration treatment. Of that group, three waited more than 500 days, one of whom waited 589 days. What do you think happens to someone living with severe mental illness who “awaits transfer” for 400 and more days?

Of the eleven plaintiffs, seven are African American. Two are women, both of whom are African American.

L.C. is a Black woman in her mid-20s “who suffers a mental impairment.” She’s been in and out of the criminal justice system. On November 13, 2014, L.C. was found incompetent to stand trial. After not becoming competent at the Philadelphia Detention Center, the court committed L.C. to competency restoration treatment on February 12, 2015. “L.C. has been detained for more than eight months (over 250 days) in the Philadelphia Detention Center since the order, awaiting an opening for treatment.”

What is like to await an opening? “L.C.’s mental state has deteriorated substantially during her stay at the Philadelphia Detention Center. In November 2014, L.C. was not competent but she was conversant with her public defender. In December, L.C. was screaming answers to questions, seemingly trying to talk over whatever she was hearing. By February 2015, L.C. had declined severely. She still screamed answers to her lawyer’s questions, but now the answers did not make sense. She also could not remain seated. In early June, she refused to see her lawyer at all. By late June, she sat through an interview sucking her thumb, refusing to make eye contact, and staring blankly. In late August, L.C. would not respond to any questions from her lawyer.”

On June 26, 2014, Jane Doe, in her early 40s, was found incompetent to stand trial. 480 days later, nearly 16 months, Jane Doe is still awaiting transfer: “Jane Doe’s mental and physical health has deteriorated in the nearly 16 months she has been waiting. She has lost noticeable weight. Prior to her most recent confinement at the Philadelphia Detention Center, Jane Doe would have discussions with her lawyer about her case. For the past year or more, she has refused to discuss the case and instead talks about having aliens and space ships in her body, and about being married to Jesus Christ. She has become much more delusional.”

According to ACLU of Pennsylvania Legal Director Witold Walcak, “Our clients in this case are the forgotten among the forgotten. Most of these people have no family, friends or champions in their lives, and no one listens or understands them; they truly are voiceless and defenseless, unable to challenge their unjust and blatantly illegal imprisonment.”

Jane Doe, L.C., J.H. and all the others are now voiceless and defenseless. They weren’t when they were arrested. They were all at varying levels of discursive competence. Each could talk with his or her attorney. They simply needed help, treatment, and the embrace of the human. Instead, they were cast to the Commonwealth rung of hell, a factory that crushes bones, souls and minds in order to produce anguish, delusion, silence, after which all is blank.

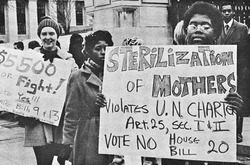

(Photo Credit: Stephanie Aaronson / Philly.com)

_LRG.jpg)